The Unlikely Global Rise of Chinese Rapper Lanlao

Over the past year, Lanlao, a hip-hop artist from a low-profile city in southern China who raps in complex, accented Mandarin and whose videos abound with niche cultural references, has become one of the most successful Chinese musicians internationally.

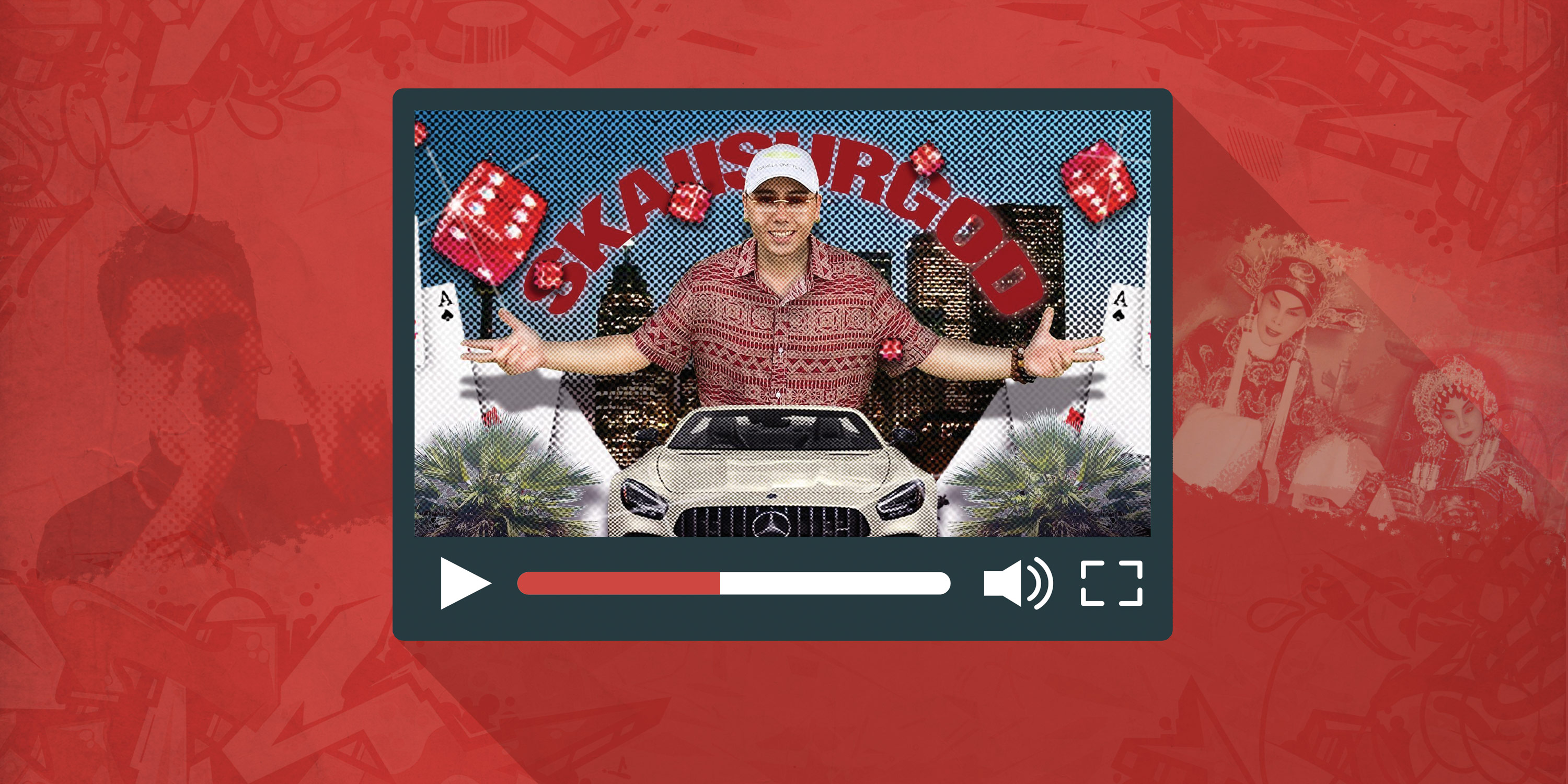

The artist, who also goes by the name SKAI ISYOURGOD, saw his unlikely rise begin with the release of “Stacks from All Sides/Karma Codes” in summer last year. The song, a commentary on wealth and inequality, first took off in China on Douyin, before gaining traction among overseas Chinese on its international sister app TikTok. Later, it spread to non-Chinese-speaking foreign audiences, with 26 million views on YouTube and with comments such as, “Understanding 0%, Vibing 100%.”

Lanlao would go on to prove to be more than a one-hit wonder, with subsequent songs, such as “Blueprint Supreme,” spawning new waves of fans from different countries, generations, and backgrounds posting videos of themselves on social media reinterpreting the track through quirky dance routines. Last month, he surpassed Mandopop legend Jay Chou as the most-streamed Mandarin musician on Spotify, approaching 5 million monthly listeners.

Beyond clever lyrics and catchy beats, Lanlao’s appeal seems to stem from his mix of American South rap style with true-to-life Chinese themes. “A key difference between Lanlao’s rap music and previous Chinese rap is that Lanlao localized the narrative of hip-hop music,” Chinese music commentator Jiang Lai, who also goes by Ravenflake, told us. “This is fundamentally different from previous Chinese rap that imitated American ghetto narratives in pursuit of ‘authenticity.’”

Lanlao — who has not confirmed his real name — was born in 1998 in Huizhou, Guangdong province, to a mother from the same province and a father from Sichuan, in southwestern China. In Guangdong, the Cantonese dialect dominates and is spoken in its capital, Guangzhou, as well as in Hong Kong, the global financial center that borders the province. The latter city’s strong cultural industries, including film, television, and music, reinforce the dialect’s position and helped give rise to the stereotype that Cantonese is the “mother tongue” of all Guangdong people.

Lanlao is part of a new wave of Guangdong artists — which includes Hoklo folk duo Wutiaoren and Hakka rock band Jiulian Zhenren — that does not identify with this dominant Cantonese culture. Using other dialects, they express a different Guangdong experience from that depicted in Hong Kong movies or Cantonese pop music. These artists also tend to fit the larger counter-cultural trend of focusing on the grit and grind of small-town China life, instead of the glitz and glamor of big cities.

This expanded, diverse articulation of the Guangdong experience gave Lanlao his initial momentum among Chinese domestic listeners. In the opening lines of “Blueprint Supreme,” for example, he portrays a classic middle-aged Guangdong “a-sok,” or uncle:

Singing karaoke in my mansion

Silver arowana swimmin’ in da’ pond

Brought my uncle a tea set

He grinds ink and wrote words with one sleeve lift

“Blueprint Supreme” — the master grabbed the pen, laid them words down fresh

“Blueprint Supreme” — brought it to the office, now the office is blessed

“Blueprint Supreme” — even Guan Gong nods his head (That’s the real deal)

Luck can’t be always leading the game

These lines describe a typical Guangdong “small-time boss” — someone who seeks wealth and success, and who prays to deities or studies feng shui to protect his ventures. It’s a character so commonplace that Chinese social media users shared videos of home décor — tea sets, karaoke systems, and calligraphies spelling out “Blueprint Supreme” — that match the lyrics.

The music video “Stacks from All Sides/Karma Codes” delivers another familiar Guangdong character — the fortune-seeking young man who dreads the karmic retribution of his blackmail and loan shark schemes:

Here in our hood, the hustlers thrive

Necklaces of jade on every guy (Got mine)

Incense burns on the altar high

We grow up, roll out white and yellow rides (Hustle!)

Devoutly worship thrice (Bows)

Hundreds enter my wallet

Guangdong was one of the earliest provinces to reap the benefits of China’s economic boom in the 1980s. But the spoils of this economic success have not been equally distributed, with most of the wealth centered in Guangzhou and Shenzhen — the heart of China’s tech industry and closely linked to Hong Kong across the border. “White and yellow rides,” for example, refers to Hong Kong car plates, a symbol of the Guangdong business elite’s mobility.

The rest of the province, including Lanlao’s hometown, developed at a slower pace. As a result, Guangdong’s income inequality is relatively high, and a facet of the region’s “small-time boss” culture is the belief that wealth is better hidden than flaunted. In the music video for “YADEA/Tiger Head Mercedes,” Lanlao plays a businessman who owns a fancy car, but prefers to ride around on an e-bike.

The wealth depicted in Lanlao’s lyrics often relates to those who left Huizhou. His city meanwhile has absorbed immigrants from less developed areas in Guangdong, who often take up low-paying manufacturing jobs. In his latest single, “Dongjiang No.3,” Lanlao describes young Huizhou hustlers gathering at a low-key late-night congee spot:

Congee stalls by East River

All big engines roar

Blue Ribbon on the table

First round — three pork rolls

Guang’s got a second kid

Ming’s stacking flats

J.K.’s jade shining bright

3D Guanyin statue

Made a name out there

But come home first

…

East River congee spot

Those clams slap (So fresh)

Eat up, fly out tomorrow

Stacks keep comin’ (Get paid)

Game’s cutthroat (So tough)

Snakes in the way

Next homecoming — red envelopes

Hundred bills each

The reference to “homecoming” tells the story of a generation that aspires to success but struggles to find it at home. In this sense, it’s not hard to see the reason behind Lanlao’s popularity in Southeast Asia’s Chinese community: this is their very backstory, for generations braving the seas to build careers in foreign lands.

Another key to Lanlao’s success among overseas Chinese seems to be Huizhou’s linguistic diversity. Just as the city’s people are mixed, so too do their dialects — Lanlao’s predominantly Mandarin delivery is studded with words in Hakka, Cantonese, and Teochew, resembling something akin to that spoken by the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia. More than a few Malaysian fans have left comments on Lanlao’s videos saying they initially thought he was Malaysian Chinese.

Listeners who understand no Chinese may also find elements of Lanlao’s music familiar. They might, for example, detect a hint of 21 Savage, a British musician who made his career in Atlanta and became a notable figure of Southern trap rap — a similarity which Lanlao does not deny. He has also talked about how Memphis rap — a Southern hip-hop style that emerged as the city’s Black population dealt with crime and racial tensions in the 1980s — influenced his music.

It’s this marriage of broad local cultural references and simple and catchy rap style that has helped secure Lanlao’s popularity. The latter turned his songs into a social media phenomenon — on Douyin, videos under the topic “Lanlao” have more than 1.7 billion views.

“His music is very expressive and well-written,” music commentator Zou Xiaoying told us, adding that he believes Lanlao’s popularity on short video platforms belies the richness of his work. “It just ended up in the short video rat race by accident.”

Even the Chinese government is enjoying Lanlao’s popularity. State-owned newspaper Global Times published a cover story on the rapper, and the Huizhou government recently used his single “Dongjiang No.3” in a promotional video.

It’s with this meteoric rise that the once small-town rapper has added another layer of mystique to his image, manifesting his own lyrics on fame and fortune into existence.

Visuals: Ding Yining.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, MLK, and Weibo, reedited by Sixth Tone)