“No”: The Magic Word in a Viral Chinese AI Remake of Snow White

Snow White and the prince lean in for the fabled kiss that should bring the end to her curse. But in this telling, it’s his blood that stains her lips.

Meet Snow White the manipulative vampire, now a social media star, teaching her followers that to be the perfect princess, one must sacrifice, be gentle, and win approval.

Her archenemy, the Evil Queen, claws her way back from the grave. No longer the villain, she sees through Snow White’s immaculate image, determined to break the spell.

Over a CGI‑slick montage, a narrator cuts in: “This was never a fairy tale. It has always been about power.”

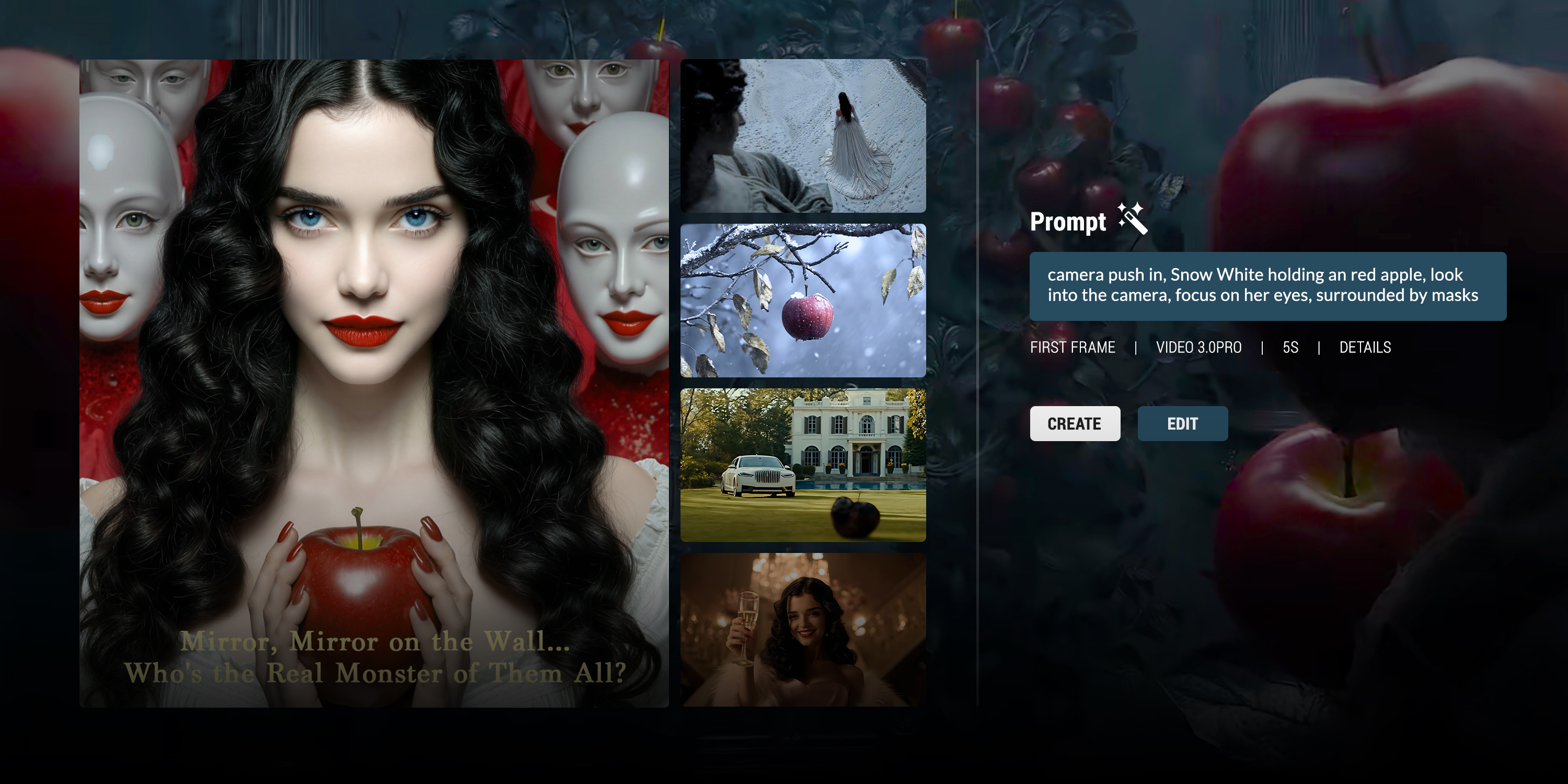

The scenes above come from “Tale of Dominion,” a four‑minute AI‑crafted viral hit with more than 3.8 million likes on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok. Styled like a film trailer, it distills Snow White’s century‑old story into a montage of sharp imagery and narration.

And in the process, it set off a broader debate about how fairy tales continue to define what women are told to be.

At its center is 39-year-old Wen Jing, a Beijing‑based screenwriter whose career spans novels, film, and TV. “Tale of Dominion” has pushed her into new visibility online, where Wen estimates over 70% of her viewers are women.

“What I really want to explore,” she tells Sixth Tone, “is whether a woman’s place in modern society is any different from her place in traditional fairy tales. And if it is different, why are these old characters still our idols?”

The idea took root closer to home. After Wen retold the story of Snow White to her 4‑year‑old son, he turned to her, baffled, and said: “Why is Snow White so stupid?”

He didn’t understand why she kept trusting the older woman. “In kindergarten,” he said, “teachers tell us never to open the door to strangers.”

Then came the harder question: “Are all girls like that?”

Breaking the spell

Not long after, Disney’s live‑action Snow White remake, released this past March, promised a fresh take on the princess. But as Wen watched, she saw the same old story: a silent, gentle girl, waiting to be rescued.

“The only character with a clear motive is the Queen,” Wen says of the remake. “Snow White wins purely through kindness, by inspiring others to help her. But she has no real agency, no voice.”

It pushed Wen back to the stories she grew up with. “In so many of these stories, the princesses have no voice at all,” she says. “First, they can’t decide their own fate. Second, they aren’t allowed to speak up, explain themselves, or fight back. They must wait to be saved.”

At her son’s kindergarten, the problem felt closer. “There are 24 children in the class, 18 of them girls. On Children’s Day, at least five dress as Elsa (from “Frozen”) and around 10 as Snow White. But what if she shouldn’t be their idol?”

That question drove Wen deeper into the character. “There are two ways to explain Snow White. Either she’s unintelligent, or she’s the one writing the story behind the scenes. Maybe Snow White isn’t even a woman — maybe she’s an idea, a carefully constructed vision of femininity.”

Wen chose the latter.

In “Tale of Dominion,” Snow White still looks every bit the storybook princess — flawless, composed, instantly recognizable. But here she controls the narrative, a perfect public figure, always adored. And the Evil Queen, still holding the magic mirror, becomes the truth‑seeker determined to break the illusion.

To Wen, the mirror symbolizes perspective, a way to see past the story as it’s been told. In Grimm’s tales, she says, “evil women” are often just women with strong opinions, unwilling to conform — and maybe because of that, they become villains.

She also wanted to explore what most fairy tales ignore: What happens to the princess after the wedding? Is her life truly the perfect ending, or just another illusion?

In one scene in “Tale of Dominion,” a glass slipper sits on a windowsill, gleaming in the light.

“Think about it,” Wen says. “A man dances with you for three nights, swears he loves you, but can’t even recognize your face. He only knows your shoe. In a system built on discipline and control, marrying this so‑called prince — can that really be happiness?”

Wen’s world

That glass slipper is just one of many striking images in “Tale of Dominion” that bring Wen’s dark fairy tale to life.

Bathed in dark gray tones and marked by stylized transitions, the video lingers on details: Snow White’s inscrutable expression, the faint glow in her eyes.

One memorable moment shows a red apple falling and rotting slowly as the background shifts seamlessly from medieval forests to scenes from a world at war, and from sprawling modern cities.

Behind the cutting‑edge CGI was an exhausting manual process. Every facet went through Wen and her partner, screenwriter and AI creator Huang Xiaodan — from writing and image generation to video synthesis, sound, and voices.

Most nights, she worked in silence after her son was asleep, the hours slipping toward dawn. Some mornings, she’d glance up from her desk to find the first light breaking outside her window.

“Tale of Dominion” took six months to complete, far longer than a typical project. The script took three days. The rest was the grind: debugging AI, stabilizing characters, adjusting to each new model update.

“I saw light in it while making it,” Wen says. “I believed the path forward was bright, so I never gave up.”

On Douyin, most comments praise Wen’s skill: “I thought this was a new Western drama — but it’s AI‑generated.” Another writes, “Liberal arts majors can also train AI — the storyteller behind this must be a literary genius.”

Many guessed correctly. Wen studied at the Savannah College of Art and Design in the U.S., worked as a photographer in Hollywood, and began writing novels a decade ago. In 2017, tech conglomerate Tencent bought one of her books for 10 million yuan ($1.38 million) — a story about a protagonist who loses her memory and name, and gradually uncovers unique abilities and a tangled family history while searching for her identity.

But the windfall didn’t last. Most of it disappeared in a failed investment. “Maybe it was never really meant to be mine,” she says. “People in the cultural field shouldn’t try to play the money game.”

By 2020, Wen had shifted to writing film and television scripts. Her breakthrough came in 2024, when she won first prize in the fantasy category of an AI video contest.

This year, she claimed Best Sound Design at the Beijing International Film Festival’s AI‑generated content section, and another of her videos was shortlisted in the sci‑fi short film category at Cannes.

The wins pulled her deeper into AI. Half her time now goes to commissioned scripts, the rest to AI videos.

To Wen, AI makes imagination tangible and allows her to create from home. As a former camera operator, she knows the physical demands of traditional filming: heavy equipment, long shoots.

“AI gives us equal footing,” she says. “In the past, filming was a male‑dominated industry. But with AI, it’s all about creativity. You’ve got a computer. I’ve got a computer.”

Since the video went viral, praise has poured in. Many shared their stories, calling her inspiring.

She pushes back at the idea of being a role model. “I don’t think real freedom means having a great career or major achievements,” she insists. “That’s just another kind of burden. Real freedom is being able to do what you want. Once you can support yourself and live your life, you’re free to chase whatever you want.”

She already has her next world in mind. A “Prince Universe,” glimpsed in “Tale of Dominion,” will bring Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and others back to the battlefield, rewriting their endings.

And in Wen’s world, there’s only one magic word.

“No to moral judgment. No to being molded. No to slut shaming,” Wen says. “The moment you learn to say ‘No,’ you gain your magic.”

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Visuals from Wen Jing, re-edit by Sixth Tone)