Chinese Scientists Save Patient Using Pig Liver Outside the Body

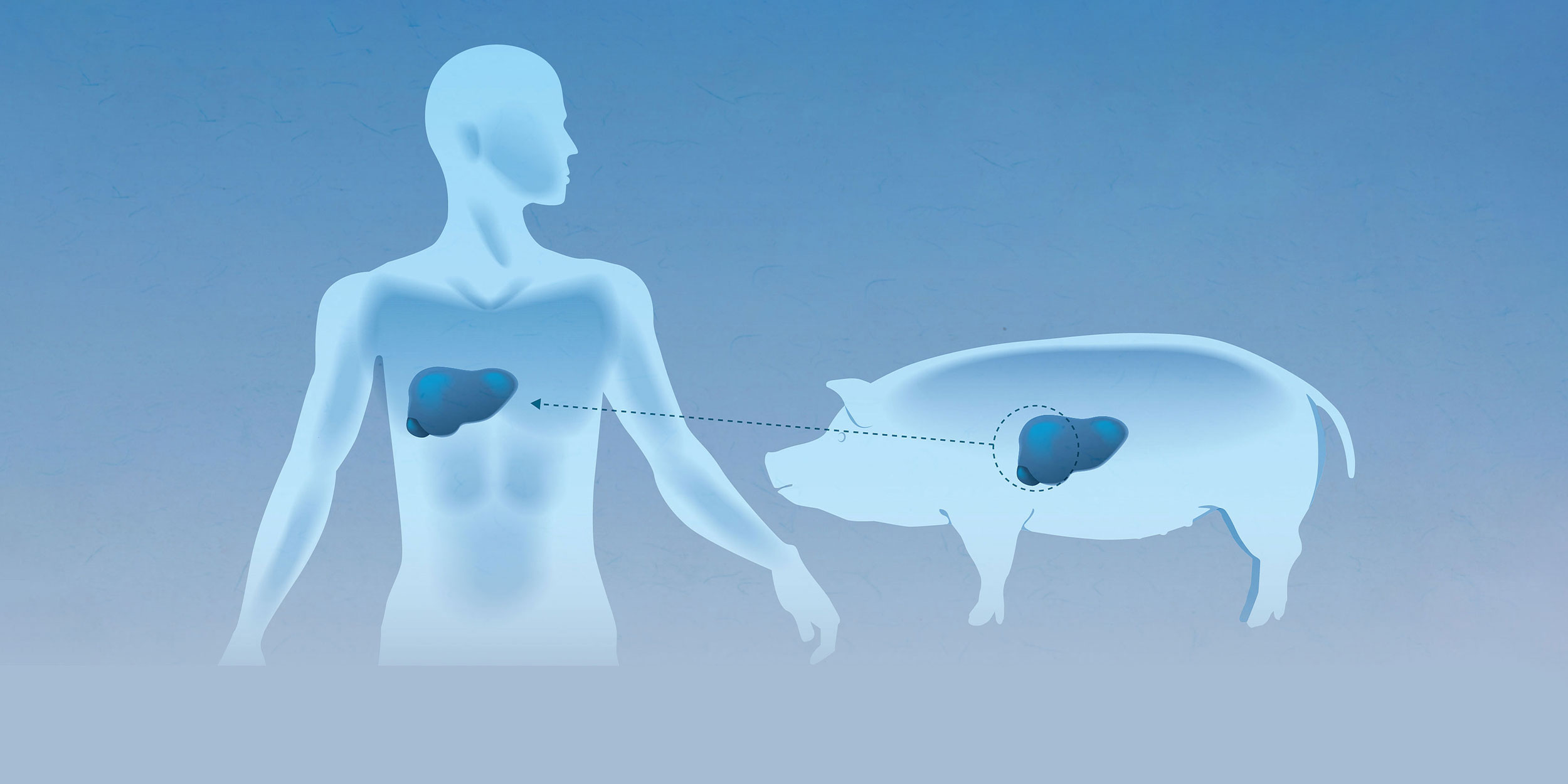

Chinese scientists have, for the first time, reversed acute liver failure using a gene-edited pig liver kept outside the patient’s body.

The procedure was announced Feb. 4 by Xijing Hospital, an affiliated hospital of Air Force Medical University in the northwestern city of Xi’an, and was carried out as part of a clinical trial.

Previous research on using animal organs in humans has primarily involved implanting pig organs directly into patients, a process that carries a high risk of immune rejection. While gene editing has reduced some forms of rejection, strong immune responses to animal organs remain a major challenge.

In the new approach, the pig liver remained outside the patient’s body, significantly lowering the risk of immune rejection. A circulation device connected the animal organ to the patient’s circulatory system, allowing it to temporarily take over key liver functions, including detoxification, synthesis, and metabolism.

The pig liver used in the procedure had six genes edited to increase compatibility with human tissue. It was cultivated by Chinese biotech firm ClonOrgan, while the extracorporeal circulation device was developed by a team from the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University in southern Guangdong province.

The system can keep a pig liver functioning outside the body for up to two weeks.

According to the hospital, the pig liver performed well, generating about one-third of the bile typically produced by a human liver. Nearly three days after the procedure, the patient’s key liver function indicators had improved significantly.

As of Feb. 5, the patient’s vital signs were stable, with physiological and biochemical indicators approaching normal levels, the hospital said.

The new technique can give patients time to wait for a human transplant or for their own liver to recover, ClonOrgan founder Pan Dengke told local media.

He Xiaoshun, a professor of surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, said extracorporeal liver support can stabilize patients and improve conditions for subsequent transplantation.

“For patients with reversible conditions, such as drug-induced liver failure, this approach can also help the patient’s own liver repair itself without the need for a transplant,” he said.

Organ transplantation is a critical lifeline for patients with end-stage organ failure, but shortages persist, particularly for livers.

More than 25,000 patients were waiting for liver transplants in China in 2024, while just 7,200 liver transplants were performed that year, according to the China Organ Transplantation Development Foundation.

China has accelerated research into animal organ transplantation — particularly pig organs — in response to the shortage. Since 2022, Chinese research teams have reported advances in gene editing, organ preservation, and immune control, enabling experimental transplants of pig hearts, kidneys, and livers into humans.

Editor: Marianne Gunnarsson.

(Header image: VCG)