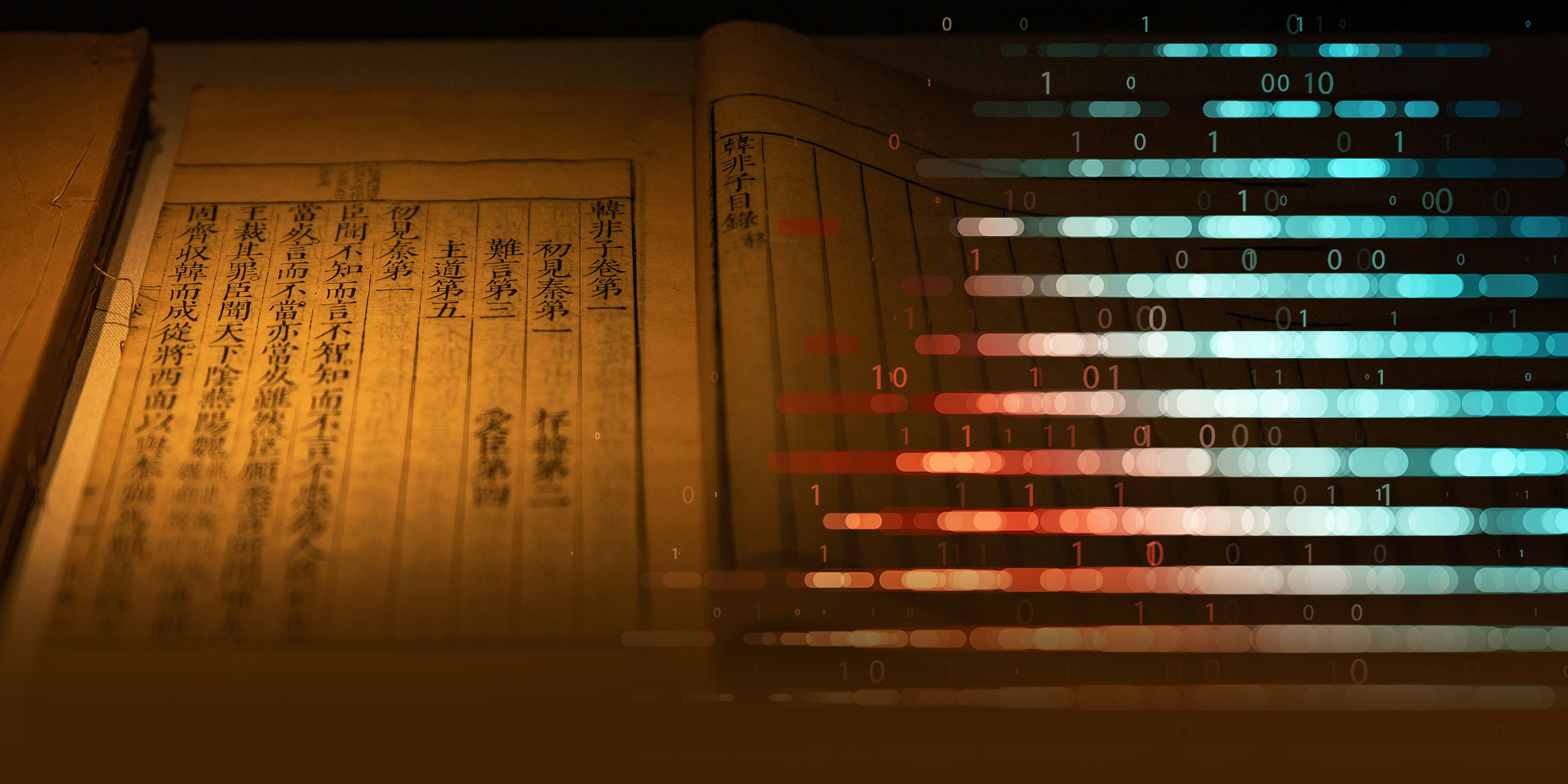

How AI Allows Us to Talk With Ancient Chinese People

To study the cultures of the past, historians rely on closely reading old texts. Did the people living along the Yellow River more than 2,000 years ago think they should stick close to their family, or that they should be more independent? Ancient books can tell you.

But hunting for such clues is painstaking work. And if you want to then analyze how cultural viewpoints have shifted across centuries or millennia, the amount of reading you will have to do grows to be nearly impossible.

Enter AI.

For a recent interdisciplinary study I conducted with my collaborators, we tasked an AI model to comb through almost 10,000 historical Chinese texts — the largest such use of AI to date. This way, we could measure how Chinese cultural psychology, especially ideas about cooperation and morality, shifted over time and across geographies.

Our study drew on two datasets. The first comprises over 7,000 books across genres and historical periods, from the start of the Spring and Autumn Period in 770 BC to the end of the Qing empire in 1911. The second included over 2,000 local gazetteers from late Imperial China, representing 270 prefectures across the country.

We built a computational pipeline that allowed us to ask questions of historical texts similar to how modern psychologists conduct surveys.

For example, in our questionnaire, one item for measuring individualism reads: “It is very important to me to express my views even when they differ from those of my friends.” For example, the AI model found this passage from a Qing-era book: “I often enjoy expressing my own views, disdainful of following others in matters of right and wrong.” Crucially, AI technology can also identify passages that aren’t exact matches but are still relevant.

The AI model then gave them a score for how strongly the writer agreed with the statement from our questionnaire — for example, did they somewhat agree, or strongly agree?

The texts were scored along dimensions like collectivism, independence, honor culture, authority, loyalty, care, moral egalitarianism, and norm tightness. In a way, we let the AI model “listen” to the voices of long-dead authors. In the end, we could deduce the values of their time from their writings.

What our quantitative analysis based on large datasets revealed were challenges to long-held assumptions about Chinese culture.

It shows that cultural psychology in China did not progress along straight lines. Rather, it ebbed and flowed across centuries and varied sharply between provinces, challenging the stereotype of a timeless “Chinese mindset.” Changes in the climate and the economy had noticeable effects. When the climate cooled from the third to the sixth century and lowered grain yields, collectivism declined, for example.

While past research has shown that labor-intensive rice cultivation strengthened cooperation and collectivism compared to communities that grew wheat, our findings suggest a broader dynamic. We found that, across regions of premodern China, whether a community farmed or herded animals played a much more decisive role in its views toward collectivism.

Our findings also shed new light on how family structures shape the human mind. Much of the past research in psychology has assumed that tight kinship — large clans, extended families, and close-knit lineages — promotes parochialism. In other words, people help relatives but care less about strangers. Western evidence supports this view, demonstrating that intensive kinship norms are often associated with weaker universalistic values. Studies of medieval Europe, for instance, suggest that more universal forms of trust and cooperation began to take root only when the Church curtailed marrying within the extended family.

Our study of Chinese history tells a different story. We found that in premodern China, where extended families and clans dominated social life, intensive kinship was not just linked to in-group loyalty, collectivism, and authority, but also to a surprisingly high level of care. Confucian ideals like “Honor the elderly and cherish the young in other families as we honor and cherish our own” expanded family-based benevolence into broader moral concern. Instead of narrowing the circle of compassion, kinship sometimes widened it.

Some humanists worry that AI-driven approaches risk reducing culture to numbers. To some extent, it’s true: a model cannot replace the nuance of close reading, nor can it capture irony, ambiguity, or context the way a trained historian can.

One of the ways we answered such concerns and tested the validity of our method was by comparing the AI-based scores with independent historical evidence.

We checked whether our findings about kinship intensity correlated with how well family histories were documented in a certain region, an indicator of strong clan organization and kinship ties. We also looked at whether the officials whose writing we identified as having traditionalist values did indeed oppose reform measures, and vice versa. In both cases, the results supported the validity of our approach.

Also, one major benefit of using AI for such work is that it allows for consistent application of the same set of standards. Our work is one of the earliest successful uses of this methodology, even though we applied modern Western psychological measurements to ancient China. This further underlines how AI makes cross-cultural comparisons with the same set of standards — something previously unimaginable — a possibility.

One advantage of studying China is the sheer continuity of its historical record. Unlike many regions where archives were lost or fragmented, Chinese textual traditions — from Confucian classics to local gazetteers — form an unbroken chain of cultural memory.

This allows us to observe psychological change across centuries and even millennia, rather than just across decades. Think of it like tree rings: each layer of text preserves traces of the mindset of its age. AI helps us read those rings at scale.

Rather than a threat, we see AI as a complement. Quantitative analysis can reveal patterns invisible to the naked eye, while traditional scholarship provides the depth and interpretive power to explain them. Together, they can enrich our understanding of how human psychology has co-evolved with institutions, economies, and environments.

The dialogue between AI and the Humanities has only just begun. Our study shows both the promise and the challenges: AI can indeed help us “survey the dead minds,” but only when guided by careful theory, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and respect for the complexity of the past.

By listening to the echoes in old books, and by letting machines help us hear what we might otherwise miss, we move one step closer to understanding how culture shapes mind — and how mind shapes culture.

Portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)