In China’s ‘Sympathy Economy,’ Trauma Finds a Livestream Stage

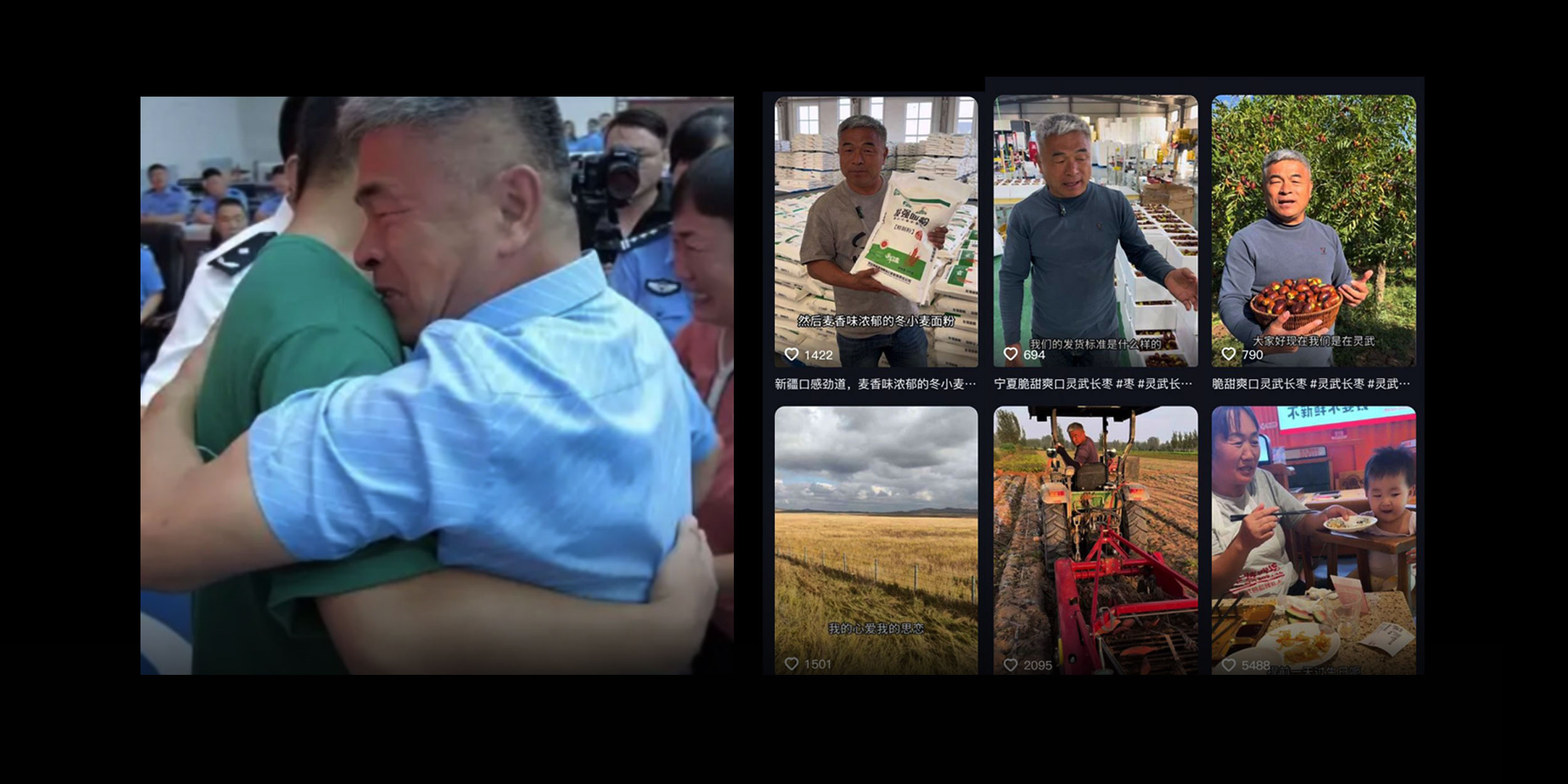

For 24 years, Guo Gangtang rode his motorbike across China in search of his abducted son, a quest so relentless it cost him 10 bikes and inspired a hit film.

When father and son were finally reunited in 2021, Guo became a national symbol of grief, endurance, and hard-won hope.

Today, he appears on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, livestreaming from village fields or farmers’ markets, selling bags of flour or pumpkins to thousands of viewers.

Among them is Li, a 37-year-old from eastern China’s Shandong province who says she prefers his pitch to celebrity sellers chasing quick profits. “He’s always selling local farm products to help farmers,” she said. “That feels down-to-earth and genuine.”

Guo is part of a growing wave of livestreamers who lean on public sympathy to build an audience. From parents once searching for missing children to families caught in public tragedies, many are turning empathy-driven attention into viable businesses, a phenomenon that has come to be known as China’s “sympathy economy.”

Yet in recent months, their rise has also drawn sharp scrutiny, as the blending of grief and commerce raises uneasy questions about exploitation, authenticity, and whether trauma can — or should — be monetized.

Victims-turned-livestreamers

China’s livestream e-commerce market reached an estimated 5.8 trillion yuan ($815 billion) in 2024, according to market research consulting firm iResearch. Driving this boom are millions of livestreamers — from celebrities to lesser-known influencers.

Within this vast ecosystem, a distinct sector has emerged in recent years: livestreamers who transform personal tragedies, ranging from human trafficking to violent crimes, into commercial success.

Families impacted by abduction and human trafficking represent the largest group in the trend.

Among these is Xie Qingshuai, who was abducted as an infant in 1999 and reunited with his birth family in 2023 after being found using AI-powered facial recognition. His homecoming stirred widespread sympathy across China, symbolizing a story of resilience and providing closure in a society where such reunions remain painfully rare.

Xie’s debut livestream in 2023 grossed more than 10 million yuan in a single night. By late 2024, he had hosted nearly 100 sessions, generating estimated sales of up to 243 million yuan, according to livestream e-commerce data provider Chanmama.

His case opened the floodgates for other victims. The family of Xie Haonan, who had also been trafficked as a child, generated more than 100 million yuan in sales and gained over half a million followers during their first livestream in April this year.

Yang Niuhua, widely known for helping police capture serial child trafficker Yu Huaying, became a livestream host alongside her family, reportedly bringing in between 7.5 and 10 million yuan in sales during a single session in May, 2023.

Similarly, the mother of Jiang Ge, a Chinese student murdered in Japan, as well as the parents of actor Qiao Renliang, who died by suicide after battling depression, have taken to livestreaming platforms to share their experiences and reportedly seek justice.

Jiang Han, a senior researcher at the Beijing-based think tank Pangoal, told Sixth Tone, “(These livestreamers’) traffic is built on authentic trauma narratives. That establishes moral legitimacy. For viewers, purchasing products is not merely a consumer act but is also … imbued with moral significance.”

Li said her purchases are less a transaction than a gesture of solidarity with Guo and his family — a small contribution to someone whose pain she once shared from afar. “Finding a lost child is like looking for a needle in a haystack,” she said. “I really sympathize with them.”

Brands are also drawn to these livestreamers for their social value. By partnering with individuals whose stories carry deep emotional weight, companies can quickly project a more approachable, “people-first” image while associating themselves with narratives of resilience and positivity, according to Jiang.

Yet the long-term benefits of such collaborations remain uncertain. To Jiang, loyalty in these livestream rooms tends to center on the host rather than the product, making it difficult for brands to build lasting connections or cultivate repeat buyers.

Between empathy and exhaustion

As the sympathy economy expands, so does the controversy surrounding it. While some followers embrace these livestreamers as symbols of goodwill, others criticize them for blurring genuine storytelling with commercial exploitation, highlighting the fine line between empathy-driven narratives and profit seeking in the livestreaming space.

For Li, the debate feels distant. She has followed Guo since the days when his motorcycle-bound quest to find his son became a national symbol of endurance. Now, when she buys a bag of flour from his livestream, she feels the continuity of that story.

Huang Anran, a mother from China’s southwestern Guizhou province who continues to search for her abducted daughter, told Sixth Tone she holds a neutral view — as long as livestreamers refrain from misleading consumers with fabricated stories, she believes they are doing nothing wrong. At the same time, she hopes those who gain from public sympathy will raise awareness on trafficking and other crimes.

Others, however, have voiced doubts — questioning the ethics of turning personal tragedy into profit and criticizing livestreamers for driving up product prices.

Zhang Ling, a 15-year follower of human trafficking stories, said her sympathy began to sour, witnessing those who once wept over their stolen children now hawking products via livestreams.

“For them, the grief that commanded the public’s compassion has become a marketing hook — a way to turn sympathy into traffic and sales,” the 50-year-old said.

The core audience of such channels often consists of middle-aged women and mothers, an activist critical of the trend told Sixth Tone. Livestreamers typically focus on low-cost daily necessities and household goods priced between 10 and 100 yuan — products easy for emotionally driven viewers to buy on impulse.

“Consumers see it as charity — paying a small emotional premium to show support, while also gaining emotional satisfaction in return,” the activist said, asking to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation.

Merchants, they added, favor working with such influencers because their audiences are less sensitive to inflated prices and reluctant to request refunds even if there are quality issues. “Returning an item would feel like returning their emotional belief,” they said.

And, they said, when compassion is monetized, it takes the spotlight away from those still in need. “Those who truly need help may become marginalized, with no space to voice their struggles.”

Amid such controversies, platforms are tightening oversight. In May, Douyin suspended all monetization methods — from in-stream tipping and product sales to sponsored content and advertising — for accounts tied to ongoing high-profile cases.

State media, too, has highlighted the risks of “performative sympathy” in livestreaming, warning that such narratives erode public trust. By December, China’s top internet watchdog had launched a nationwide campaign to curb false information and “unsuitable content” on short-video platforms.

For many viewers, however, the damage has already been done. Zhang, the once loyal follower of family-reunion accounts, has since unfollowed them all. “The end of the search for a lost child is the beginning of harvesting leeks,” she said, using the Chinese slang term ge jiucai, describing the exploitation of ordinary people for profit.

“These performances didn’t just sour my feelings — they froze the hearts of everyone who once cared.”

Editor: Marianne Gunnarsson.

(Header image: Guo Gangtang embraces his son during the ceremony in their hometown Liaocheng, Shandong province, July 2021; right: Guo Gangtang’s Douyin account. From Liaocheng Police and Douyin)