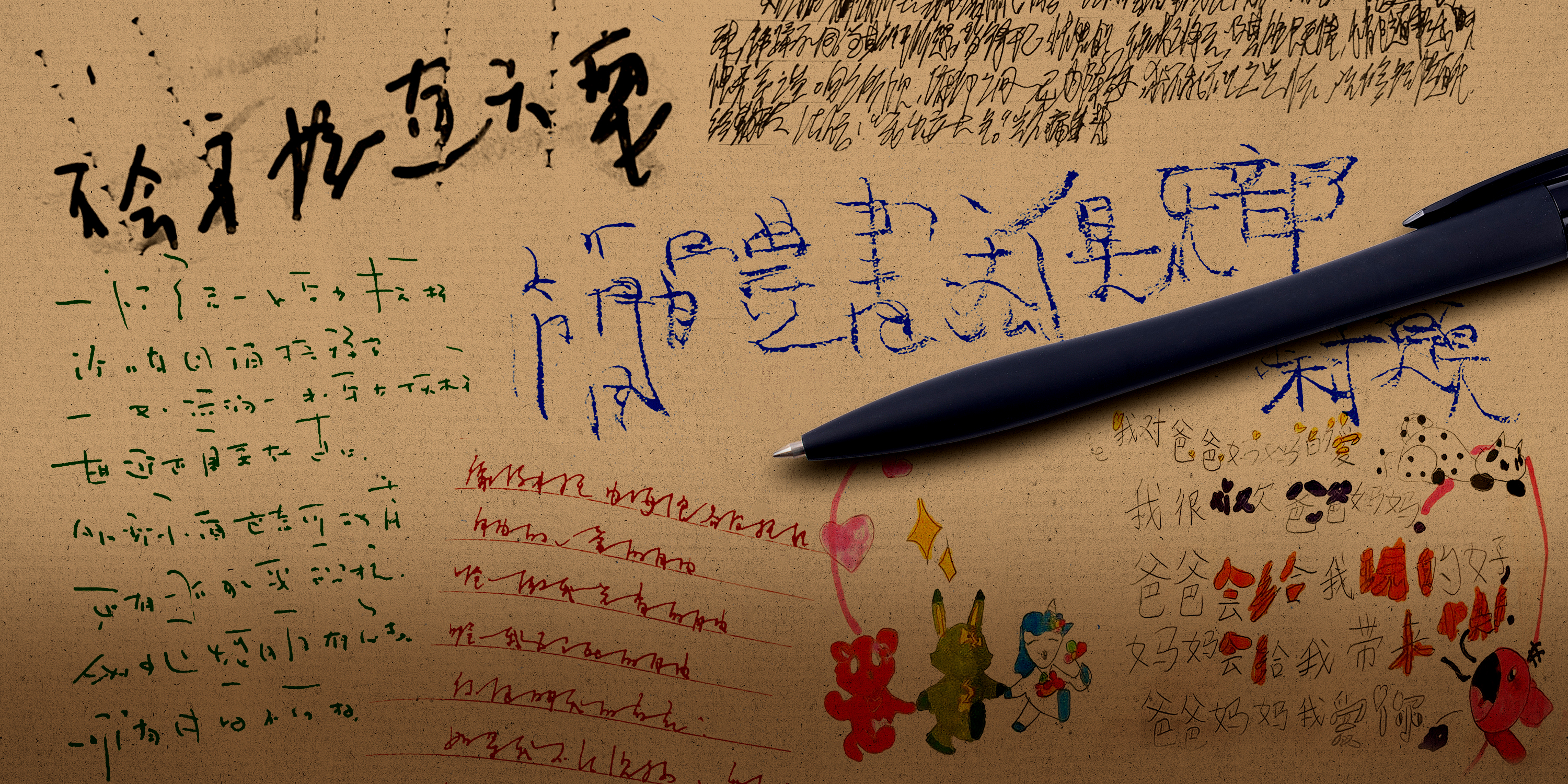

China’s ‘Worst Handwriting Group in History’ Rewrites Grief

“Please help me recognize the last word my father left me,” wrote a forum user nicknamed “Jiang Bian” on the first day of 2024, posting a photo of barely legible handwriting. “He couldn’t speak; his hand couldn’t hold a pen. All he could manage was a faint stroke of his finger.”

A reply came immediately: “He’s wishing you a Happy New Year.” Another user agreed, “It’s a very typical way of writing the first Chinese character ‘xin’ (new) in cursive for his generation.” Dozens more replies followed that night, amounting to nearly 100 strangers collectively easing a daughter’s grief.

The forum — dubbed “The Worst Handwriting Group in History” — was founded in 2019 on social platform Douban as a lighthearted space to share messy scrawls.

But in 2023, the online space transformed, becoming a refuge for people seeking help in deciphering the fading words of passed relatives, turning casual banter over handwriting into a community archive of memory and space for shared pain and loss.

“Grandfather has passed. Study hard, work diligently, and always remain faithful to the Party,” reads one scrawl. After careful debate in the comments, the group managed to decode the message — a hidden letter finally brought to light years after it was written.

Another note reads, “Observe funerals without gongs, drums, or firecrackers; don’t accept any monetary gifts; mark the day in quiet reverence; abolish irrational old customs.” Thanks to crowdsourcing, a grandfather’s words were pieced together, reconnecting a family across two worlds — life and death.

Since its conception, the forum has grown to more than 200,000 members. The group’s profile declares: “If your handwriting is terrible, sorry — we have worse! Here, bad handwriting makes you a king.” Its rules explain that the community was created as a “utopia” for those often ridiculed for their penmanship. “Even if your handwriting isn’t good, you still have the right to write — and to bring joy and meaning to others.”

The group started as a playful space to mock scribbles resembling a child’s handwriting, caterpillar-like fonts, and leaders’ indecipherable cursive. Members once traded biting jokes, comparing posts to spider webs, swans riding bicycles, and people doing yoga.

Among them was Ji Mengyu, then a university education major embarrassed by her own messy blackboard writing. Drawn to the group’s lighthearted banter, she gradually regained confidence and eventually took over as its operator.

The first help posts began appearing in the summer of 2023, but attracted little notice. Ji pinned some to the top, yet traffic remained low.

The turning point came in October, when one user shared her father’s nearly illegible scrawl from an ICU bed. Members pored over the words and suggested he might be communicating that he had something lodged in his throat. The family relayed the tip to doctors, who confirmed the diagnosis. Within days, the man was moved out of intensive care.

“It was like saving a life,” Ji says.

As the number of help posts surged — sometimes dozens in a single day — the group’s front page was soon overwhelmed by stories of illness and death. Members who were looking for lighthearted fun pulled away in the face of an endless stream of grief. Ji understood. “You’re tired after a long day and open your phone to relax, but all you see is separation and loss. You empathize, but you also want to escape.”

She considered whether to move the help posts to another group, but worried they would once again be ignored. In the end, she created a centralized forum where all help posts would be gathered. The main page became lighter, conversations resumed, yet those seeking help were not forgotten.

Ji also noticed that many help post accounts belonged to one-time visitors. Still, Ji could read their emotions between the lines.

She recalled one member who poured out a long story: his grandfather’s death, his illness, and the discovery of only 81 yuan ($11) left in his grandfather’s old belongings. “Objectively, these details don’t help in deciphering the words,” Ji says. “But they needed to talk. Words are simply a vehicle for emotion — pain, longing, helplessness.”

Most of the posters, she observed, were young, facing the loss of a loved one for the first time. “I sensed that they knew, rationally, the words were unreadable. But emotionally, they couldn’t accept it.”

Ji remembered one group member’s response to an illegible word: “It could be any word you need, no matter if you’re happy or sad.”

In the beginning, Ji felt unsettled when posters never came back. Now she sees it differently. “When they don’t look back, it means they’re living their lives — perhaps busy with work, or caring for family. They’ve moved on. And you understand that everything will pass.”

Despite the group’s reputation for “saving lives,” Ji downplays her role. “I haven’t done anything great. All they need to know is that there are people in this world willing to help — not just one person, but countless people.”

For her, the most moving form of kindness lies in small, almost imperceptible gestures. She compares her role to helping someone with a heavy suitcase or carrying too many books. “That kind of kindness is unconscious, subconscious,” she says.

In truth, Ji confesses, nine out of 10 posts seeking help cannot even be deciphered into complete sentences. “The handwriting is so fragmented it barely connects,” Ji admits. But she doesn’t see it as a failure. “The outcome isn’t important. The very existence of this group is meaningful.”

This shift in perspective transformed her. She once despised her own poor handwriting, even looking down on others who wrote badly. But now, as a newly fledged Chinese teacher, she has stopped demanding that her students “write beautifully.”

She compares her change of heart to the famous “Eulogy for My Nephew,” written by the calligrapher and military general Yan Zhenqing during the Tang dynasty (618–907). “The front is neat, the back a mess of scribbles. It’s precisely because it looks ‘bad’ that you can see the author’s true emotion.”

“I want their effort, not the result,” she says.

Editor: Marianne Gunnarsson.

(Header image: Visuals from Douban and reedited by Fu Xiaofan/Sixth Tone)