‘You Are the Best’ Is Jiang Wen Writ Large

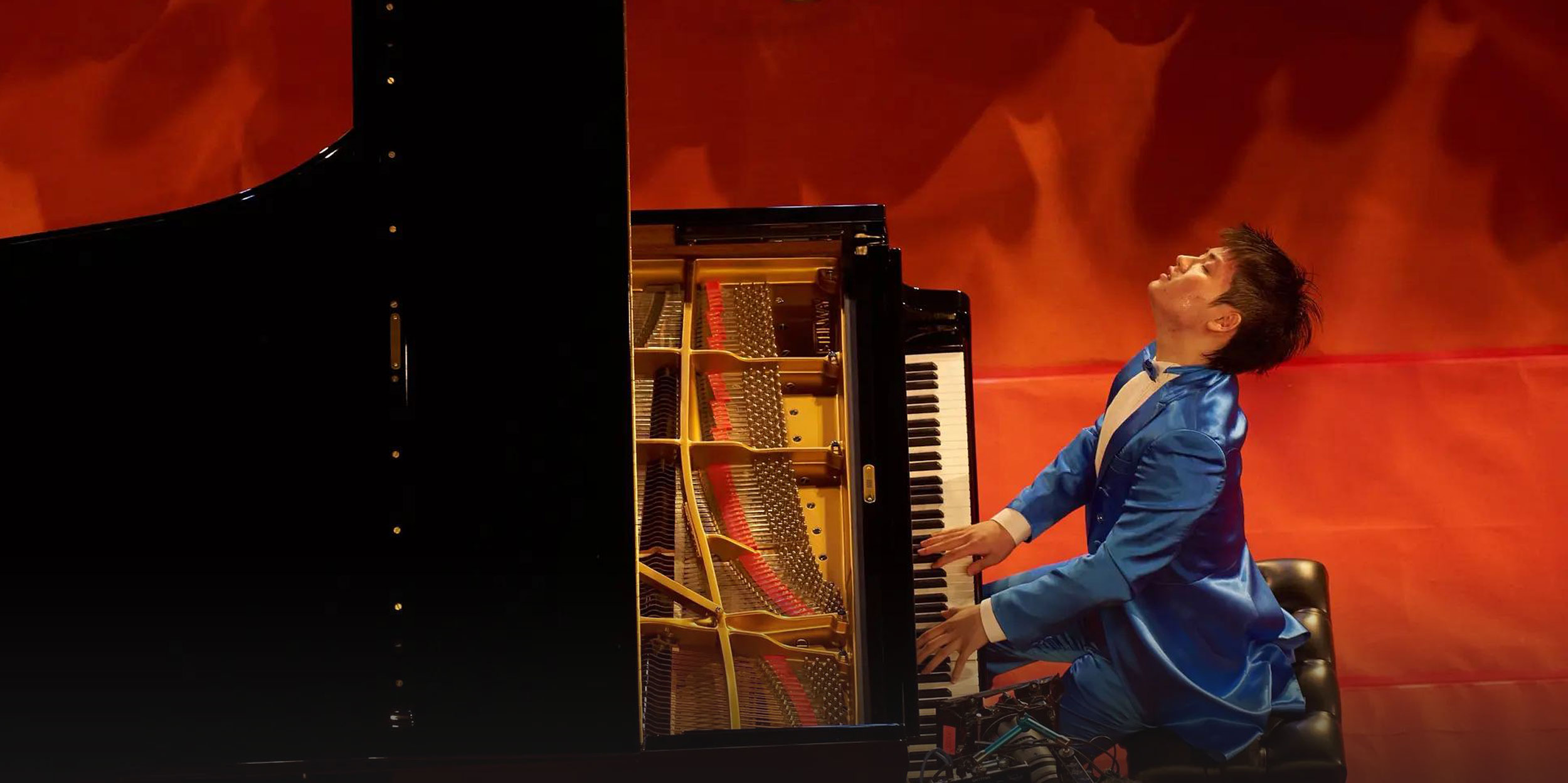

After a seven-year hiatus, Jiang Wen returned to the big screen this summer with the Lang Lang biopic “You Are the Best,” about the Chinese pianist-celebrity’s rise to fame.

As one of the most celebrated Chinese filmmakers in recent years, Jiang Wen’s latest offering generated significant buzz leading up to its release, especially after he described it as “the best of his career.”

This was no small claim, considering Jiang’s repertoire includes movies like “In the Heat of the Sun” (1994) and “Devils on the Doorstep” (2000), as well as 2010’s “Let the Bullets Fly,” a satirical gangster flick set in the 1920s that became an instant cultural touchpoint and generated heated discussion among fans who hailed it as a masterpiece. In fact, Jiang has even described the pursuit of greatness depicted in “You Are the Best” as, “‘Let the Bullets Fly,’ but with pianos instead of guns.”

Yet despite the hype, the film fell flat both at the box office and among viewers, failing to break the 100 million yuan ($13.7 million) mark and receiving a score of just 6.7 out of 10 on rating site Douban.

While many may chalk this up to Jiang having at last exhausted his talents, there may be more to it. In fact, with “You Are the Best,” it could be argued that he expresses himself more distinctly than ever — it’s just that his approach failed to resonate with the concerns of today’s audience.

In terms of style, the film is very much in keeping with Jiang’s previous works. His trademark motifs appear, including rooftops and terraces where characters run freely, ubiquitous sunlight, and Oedipal complexes. The style is also “pure Jiang,” with its extremely fast editing, significant amount of dialogue, surrealist techniques, freneticism, and underlying political and historical references.

Jiang’s signature rebelliousness is also still evident: In the first half of the story, Lang Lang and his father were seen repeatedly challenging the music elites and the hypocritical dignity of his teachers. But the satire soon gives way to self-satisfaction, glorifying reckless gambling, instant gratification, and blind self-belief.

While “You Are the Best” is promoted a biopic about Lang Lang on the surface, at its core, it’s about his pushy father, Lang Guoren, the “chief designer” and helmsman of his son’s success, and who Jiang plays in the movie.

Unlike his previous movies, such as “In the Heat of the Sun,” “The Sun Also Rises,” and “Hidden Man,” where Jiang explores the psyche of fatherless sons, here, Lang Guoren is a domineering figure who looms large, even more so than Lang Lang’s own agency and complexity. Lang Guoren is essentially a “tiger dad,” pushing his son to reach the top and never stop striving. The film’s Chinese title — “Ni Xing! Ni Shang!” — even references this fervor, echoing Lang Guoren’s order to his son: “If I say you can do it, you can do it! If I tell you to go, you go!”

The unhealthy father-son relationship is packaged as a tale of family support, but it also acts as a proxy for the film’s rumination on the nature of chasing success. Through the father’s relentless drive, the film takes on an atmosphere of madness and excess, in some ways mirroring Jiang’s own growing agitation and urgency to deliver truths through metaphor and reference. After all, the film does not culminate in greater reflections or revelations about Lang Lang’s musical achievements — an unusual departure from typical biopic narratives.

In one interview, Jiang Wen said that he wanted to depict the single-minded pursuit of one’s dreams and present what is possible when you place no limits on yourself. Unfortunately, the film’s understanding of passion and the pursuit of the arts is mostly expressed as a need to win and not be satisfied with second place — ultimately framing this complex, obsessive pursuit of success in a positive light.

Jiang’s message in the film also gets muddled as he places outsized emphasis on Lang Lang’s heritage and innate talent. In a surrealist scene set in a large community courtyard, tens of thousands of people listen to a young Lang Lang as he floats midair and plays “Liuyang River” and “The Yellow River Cantata,” two famous Chinese folk music pieces, before an upcoming journey to the United States. Although the events of Lang Lang’s rise to fame took place in the late 1990s to early 2000s — the height of China’s embrace of globalization — the film ties this moment to greater national confidence and development, focusing on the father-son duo’s determination to defeat all international opponents.

While the film seeks to inspire audiences through Lang Lang’s success and a sense of national pride, it also uses blatant political references. Unlike “Let the Bullets Fly,” Jiang’s metaphorical game in “You Are the Best” has essentially transformed into one of almost direct allegory. For instance, the piano teacher Ou Ya — whose eccentric and strange behaviors are perplexing within the core narrative — is named after the Chinese characters ou and ya for “Europe” and “Asia,” respectively, in reference to the Soviet Union. The students that she denounces for having betrayed her seem to refer to the breakup of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, with her inexplicable parting with Lang Lang also implying China’s and the Soviet Union’s decision to go their separate ways. Other characters act as stand-ins for other locales, such as Zhuge Bole, who represents the West. When Zhuge Bole competes for Lang Lang’s “development path,” it prompts Lang Guoren to assert, “I’m the chief designer!” in a satirical moment.

Unfortunately, Lang Lang’s story and the film’s contemporary setting leave little room for such stiff and forced texts to be naturally integrated. Apart from a few die-hard fans keen to interpret these vague and cursory references, for most viewers, the continuous bombardment of information merely deviates from the movie’s themes and creates a sense of confusion, fatigue, and noise.

“You Are the Best” has as many as 4,700 shots — over three times that of the average film. However, given the plot’s repetitive nature as Lang Lang seeks out masters and then abandons them, winning victory after victory, these referential lines and jokes seem to have been added to pad the narrative. Whether he’s displaying his talent or just showing off, this excess does not help the film. Instead, it places the director above the film and audience, indulging in a one-sided, self-referential creation that exists to highlight Jiang himself.

Looking at his previous films as a director, Jiang has never expanded his creative vision beyond China’s reform and opening-up in the late 1970s and ’80s. With “You Are the Best,” a problem of his comes to light: the inability to truly perceive and explore contemporary social issues and express the era’s highs and lows to the degree he was able to in past projects.

It’s a missed opportunity that ultimately cost him what could have been an eager audience. The message in “You Are the Best” touts concepts like “winning,” “ambition,” and “striving” that cater to the notion of a nation on the rise, which likely rang inauthentic to audiences facing an economic downturn and growing fatigue and disillusionment from the relentless race to the top. Instead, the film seems to be going against the current, resulting in a work that is out of touch with most contemporary viewers. Yet perhaps none of these things matter for Jiang. After all, the film has already accomplished something: showing his most self-indulgent self.

Translator: David Ball.

(Header image: A still from Jiang Wen’s latest film “You Are the Best.” From Douban)