100 Years Ago, Beijing’s Forbidden City Opened Its Doors

One hundred years ago, on Oct. 10, 1925, the Palace Museum was officially established on the grounds of the Forbidden City, the imperial palace in the heart of Beijing. The museum’s founding, as well as the subsequent opening of the palace for public viewing, the display of the imperial collection, and the establishment of the Gallery of Antiquities were all significant achievements in the transformation of modern China and had a profound impact on the development of museums across the country and even the world.

But how did all these things happen? The story begins 14 years earlier on Oct. 10, 1911, when the Xinhai Revolution broke out. On Jan. 1, 1912, the Provisional Government of the Republic of China was established, with Puyi, the last emperor of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), abdicating on Feb. 12. With the end of the imperial system and the establishment of the Republic of China, the necessary social conditions were created for the Forbidden City’s transformation.

In December 1913, Zhu Qiqian, the new government’s minister of internal affairs, ordered the establishment of the Gallery of Antiquities, with the aim of “observing the people’s reverence for antiquity, gathering the secret, treasured relics accumulated over generations, and setting up an exhibition hall for antiquities within the city as the forerunner of a museum.” Meanwhile, the Government Gazette warned in 1913 that the cultural relics from China’s various dynasties were at grave risk from wars, floods, fires, and their outflow to foreign countries, and highlighted the government’s urgent responsibility to safeguard these artifacts. As such, the Ministry of the Interior planned to follow the example of the West and establish museums.

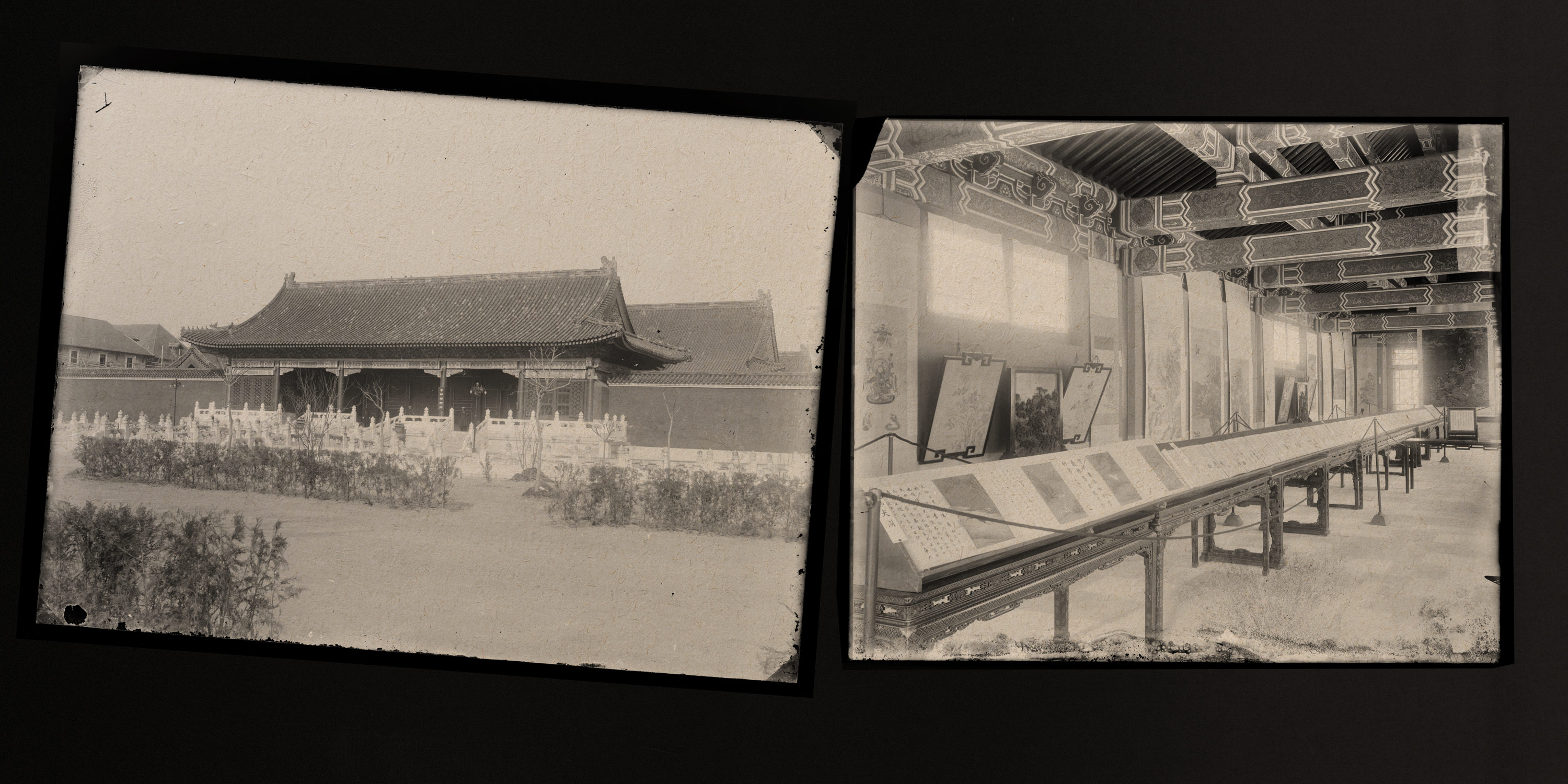

In March 1914, renovations began on the exhibition venue — Wuying Hall, a building previously used for printing books and located inside Xihua Gate, the Forbidden City’s western entrance. That’s where, on Oct. 10, the Gallery of Antiquities officially opened. Dignitaries from home and abroad attended the grand ceremony and visited the exhibition. The next day, the venue opened to the public, and over 2,000 people were admitted.

According to a report in the Ta Kung Pao newspaper at that time, Wuying Hall’s east room displayed cloisonné artworks, and the west room displayed bronze wares. Meanwhile, the main hall was hung with four works of calligraphy and paintings, alongside a photograph of then-President Yuan Shikai, and its rosewood furniture was covered with cultural relics such as bronzes, porcelain, lacquerware, wood carvings, scholars’ tools, portrait albums, and silk flowers. At the rear of the main hall, Buddha statues and scriptures were enshrined. The walls of the corridor connecting to the rear hall were hung with paintings from the early Qing dynasty. Inside the rear hall, there were jade artifacts, brocades, silk fabrics, embroidered cushions, and more. Visitors could rest on large Western-style chairs.

Two years later, a project to renovate Wenhua Hall — once a venue for religious banquets and lectures, located inside Donghua Gate, on the Forbidden City’s eastern wall — was completed. Unlike Wuying Hall, which mainly exhibited porcelain and bronzes, Wenhua Hall was home to ancient paintings and calligraphy from earlier dynasties, including masterpieces by artists Hui Chong, Wang Xi, Guo Xi, Ma Yuan, Ni Zan, Wang Meng, and Zhao Mengfu — some of them nearly a thousand years old.

The Gallery of Antiquities, which was composed of Wuying Hall and Wenhua Hall, became an artistic sanctuary during the early Republican years for people in Beijing to view ancient objects and study painting techniques. However, it’s worth noting that while Puyi had abdicated at that time, he was still living inside the Forbidden City, in the inner court to the north of Qianqing Gate. This space preserved the titles of the emperors, while political ceremonies such as the enshrinement ceremony and longevity celebrations all expressed memories of the Qing dynasty. The transformation from imperial palace to public museum was not automatic with the fall of the imperial system and rise of a republican system, as the nascent Republic of China lacked a cohesive central authority and, especially after Yuan Shikai’s failed attempt to restore the monarchy and his death in 1916, soon fragmented into the turbulent warlord era.

In October 1924, the Forbidden City was once again thrown into turmoil when General Feng Yuxiang launched the Beijing Coup, and his ally Huang Fu organized the Regency Council. On Nov. 5, the council released the “Articles of Favorable Treatment of the Qing Imperial Household,” and dispatched Lu Zhonglin, the commander of the Beijing Garrison, along with Police Chief Zhang Bi and civilian representative Li Yuying, to enter the Forbidden City. Puyi was ordered to immediately leave the palace, and all of his non-personal possessions were declared to be the property of the Republican government. That afternoon, the last emperor of China, with his wives and consorts, was escorted out of the Forbidden City.

On Nov. 7, the Regency Council established the Committee for the Disposition of the Qing Imperial Possessions, appointing Li Yuying as chairman and inviting experts to inspect and deal with the items in the palaces, stating: “All the public property should be used by libraries and museums to promote culture and ensure its long-term preservation.”

On Dec. 20, the committee held its first meeting and agreed on a set of rules for inspecting the artifacts. The document detailed the procedures and steps related to the unsealing, inspecting, registering, numbering, cataloging, and photographing of items, as well as issues concerning the inspection and supervision personnel. Due to the strong interest from all sectors of society, the committee met and issued inspection reports regularly, documenting the names and quantities of items. To satisfy the large public demand for visiting the Forbidden City, the committee released a set of provisional rules on April 12, 1925, and drew up a tour route, with the central road through the Forbidden City to be opened to the public every Saturday and Sunday afternoon.

On Oct. 10, 1925, a grand opening ceremony for the Palace Museum was held inside the Qianqing Gate. The ceremony was chaired by Zhuang Yunkuan, supervisor of the Committee for the Disposition of the Qing Imperial Possessions and a director of the temporary board of directors of the Palace Museum, who announced the museum’s establishment.

At the opening ceremony, Huang Fu, then director of the Palace Museum, also delivered a speech, expressing the significance of the museum as a public space:

The transformation of the Forbidden City from private to public was made possible by the efforts of the military and police authorities. From now on, it shall become a museum and be completely public, with those who serve within it being the public servants of the people. Today is the Double 10th Day, the National Day of the Republic of China, and will also become the anniversary day of the Palace Museum. We will celebrate them together. That is, damaging the museum is equal to damaging the Republic. We shall stand up and protect it.

According to provisional guidelines on the Palace Museum’s organization, it was composed of two subordinate divisions: the Museum of Antiquities and the Library. The Museum of Antiquities set up exhibition rooms for calligraphy and paintings, ancient bronzes, ceramics, and cloisonné and carved lacquerware in the Kunning Palace. Especially notable pieces took pride of place, such as the Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 BC) San Family Plate and the earliest known example of a jialiang, an ancient measuring device, made during the Xin dynasty (9–23). The Five Dynasties and Ten States-era (907–965) paintings “Herd of Deer in a Maple Grove” and “Flowering Reeds and a Pair of Swans” were displayed together in the same room.

The mysterious treasures that had been hidden away for centuries were now open to the public, much to the joy of people across the country. On opening day, the Palace Museum thronged with visitors. Author and artist Sun Fuxi, who visited on the first day the museum was open, vividly described the new public ownership of the Forbidden City and its ancient relics:

If you were to break a piece off of the San Family Plate or tear a strip from the Three Rarities of Calligraphy, you would feel that the loss is not only yours — it is borne by everyone. A crippled old woman might raise her peach wood walking stick and hit you, or a muddy-faced child might spit on you. You may be the owner of these things, but you do not have the right to damage any of them.

The next day, when staff cleaned the museum, they filled four baskets with the handkerchiefs, hats, and shoes visitors had left behind.

The public’s ardent interest powerfully demonstrates the historic significance of the Palace Museum’s establishment: the once closed-off and solemn imperial palace was now crowded with ordinary people, while the ancient objects that had belonged exclusively to the emperor had been granted a new audience. From then on, except for the period when the museum’s relics had to be evacuated and moved south during the WWII, the Palace Museum has stood as one of the most popular museums in China and a precious piece of global cultural heritage.

Translator: David Ball; Portrait Artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Archive photos show the Wuying Gate (left) and Wenhua Hall. Courtesy of the author)