A 969-Year-Old Pagoda, Too Fragile to Climb, Gets a Fitting Facelift

When, at dusk on a fall day in 1933, Liang Sicheng, China’s pre-eminent architectural historian, first laid eyes on the Wooden Pagoda of Ying County, he was in awe.

“When we were still some five miles from the town, I suddenly discerned — near the furthest limit the road allowed the eye to reach — what seemed a flashing jewel against a deep violet backdrop: a red-and-white pagoda, its tiered roofs suffused with the gold of the sinking sun and gently cupped by the surrounding hills,” he wrote.

Liang was traveling to Ying County, in northern China’s Shanxi province, with colleagues from the newly established Society for Research in Chinese Architecture, the first private scholarly institution in China devoted to the study of historic architecture. Its researchers had started a year earlier with annual expeditions of two to three months. They located surviving monuments, climbing and measuring them to document the rich architectural history of China.

The Wooden Pagoda of Ying County — also known as the Sakyamuni Pagoda for its dedication to Buddha — was completed in 1056 during the Liao dynasty (916–1125) and rises 67 meters. Its five primary exterior stories, interleaved with four concealed intermediary levels, create a nine-tiered timber-frame composition. Every column and beam, every set of interlocking brackets, is deliberately proportioned; tier upon tier they knit together to display the consummate ingenuity of timber construction — in which not a single iron nail was used.

Liang at once wrote to his wife, the architect Lin Huiyin: “My first feeling was sheer regret that you were not here to feast your eyes on this. Otherwise, I truly cannot imagine how many times you would prostrate yourself in admiration!” He continued, “This pagoda is a unique and magnificent work. Without seeing it, one cannot know to what limits timber construction can be pushed. I am filled with admiration — admiration for the age that created it, for the great yet nameless architect of that age, and for the nameless artisans.”

Still flushed with discovery, he led his colleagues into an exacting, measured survey: photography, plans, bracket and sectional data, then heights of each projecting eave and of the finial, the pointy ornament at the top.

The work was perilous. In an article, he recounted how, while busy on the roof during one radiant afternoon, absorbed in measurement and camera work, he failed to notice storm clouds massing: “Suddenly a crash of thunder exploded close by. Caught unawares, I nearly lost my grip on the icy iron chain, 200 feet above the ground.”

Mo Zongjiang, a colleague, further recalled that when every structural piece of the pagoda had been measured, only the finial remained. It soared more than 10 meters above the already 60-plus-meter tower, with nothing to climb save a handful of iron cables. Liang, a former student athlete, seized the frigid strands, legs hanging free, and pulled himself upward until he reached the finial and recorded its construction details.

Subsequent scholarship has confirmed the pagoda as the tallest and oldest surviving multi-story wooden pagoda. On March 4, 1961, the Chinese government included it on the inaugural list of nationally protected key cultural relics. A millennium of weathering has left this improbable survivor scarred. A formal restoration initiative entered planning in the early 1990s; survey data in 2004 revealed structural load imbalances. From 2011 onward, in the interest of safety, the upper stories were closed to the public. Only the first floor remains open.

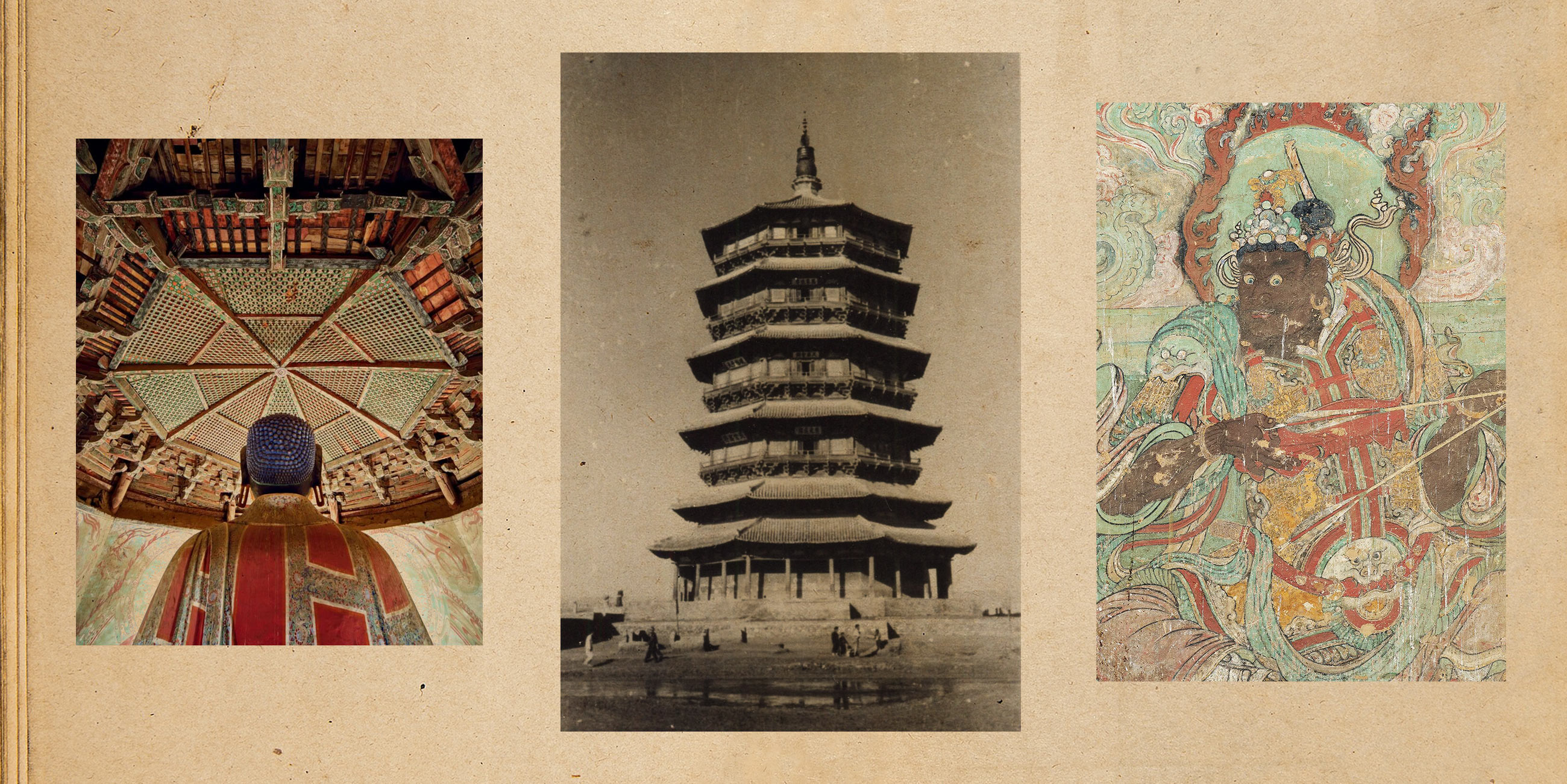

For visitors, this is a palpable loss, for the pagoda is not only a triumph of timber engineering but also a treasury of art and culture. Within it are wall paintings from successive periods, sometimes covering older works; sculpted images whose earliest layers date to the Liao dynasty; inscribed plaques, dedicatory texts, and steles; and, concealed within statues, a substantial cache of Liao-dynasty artifacts, ritual objects, scriptures, documents, Buddhist paintings, and a seven-treasure reliquary — a container of holy relics.

Few feel this deprivation more keenly than Liang Jian, who is both an executive council member of the China Cultural Relics Society and the grandson of Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin. When he first ascended the pagoda with his father Liang Congjie in the summer of 1991, Liang Jian was immediately enthralled. In the decades since, repeated climbs have continually renewed his awe at the artisans’ intelligence and the solemn majesty of Buddhist art.

Once public access to the upper levels ceased, Liang Jian began to wonder how the inner art of the structure might be recorded and shared in a way that is both accurate and aesthetic, to mitigate the regret of those who could no longer climb it. In 2022, he got Shanghai Fine Arts Publisher and the Ying County and Shanxi province governments to agree to create a high-definition visual recording of the pagoda’s interior.

Working for three months, Liang Jian’s team produced an unprecedented corpus of images. Low light, lofty murals, and the labyrinthine timber volumes made progress arduous, yet the team persisted in capturing each refined detail. The editors at Shanghai Fine Arts Publisher then undertook a meticulous three-year program of curation and refinement.

In September of this year, the book “Wooden Pagoda of Ying County,” with more than 800 photos of the pagoda’s internal art and relics, went on presale. Readers may now appreciate the poised equilibrium of force and grace in the progressively cantilevered wooden brackets; the concentric recession of the ceiling beneath the luminous central oculus; the vivid yet composed presence of the Sakyamuni statue; the sinuous garment folds and radiant nimbus motifs of the Liao murals. Even the flying celestials flanking the uppermost Buddha statue’s head — murals set at the highest inner wall, soiled by bird droppings and nearly illegible to the naked eye — emerge with crystalline clarity.

Going beyond the limits of ordinary sight, the book uses infrared imaging to bring to light long-obscured brushwork and historical inscriptions: regnal year marks on pillars to record their time of construction, Buddhist epithets in dedicatory texts, and underlying Liao mural strata concealed beneath later Qing landscape paintings, among others.

For Liang Jian, the volume embodies a hope: that this visual archive will stir broader public engagement with the preservation of cultural heritage — a momentous task in a country littered with historical buildings in need of maintenance. And it embodies the truth that, regardless of the pace of change, some artifacts of history will endure.

Portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Visuals from Shanghai Fine Arts Publisher, reedited by Sixth Tone)