Cultural Resistance: China’s Other War During the Japanese Invasion

From the Mukden Incident in 1931 to Japan’s surrender in 1945, China endured 14 years of war, marked by foreign occupation and fierce domestic resistance. What began with a Japanese incursion into northeastern China escalated into a drawn-out, nationwide conflict and one of the major fronts of WWII.

The war claimed tens of millions of lives and displaced countless more, as entire cities were reduced to rubble and civilian populations faced massacres, forced labor, and famine.

In response, the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Communist Party of China (CPC) formed a united front against the Japanese invasion. As Nationalist forces fought a series of major engagements, Communist troops led guerrilla operations and established resistance strongholds behind enemy lines.

Amid a profound national awakening, resistance took more than one form. Alongside soldiers, artists, writers, and filmmakers waged their own battle, using creative expression to document suffering, rally public sentiment, and imagine the future of a fractured nation.

At the time, Japan’s campaign extended beyond territorial conquest to include cultural domination. Slogans like “China is not a country” were circulated in Japanese propaganda. Libraries were looted, ancient texts destroyed, and Chinese-language publishing suppressed.

In response, a parallel resistance emerged, grounded in preservation, adaptation, and cultural survival. “We shall be reborn amid firelight and a sea of blood,” wrote Jiang Menglin, then-president of Peking University, in 1937.

Across the country, librarians, scholars, artists, and filmmakers worked to protect cultural memory: collecting manuscripts, smuggling books out of occupied zones, and turning creative expression into a vehicle for protest and education.

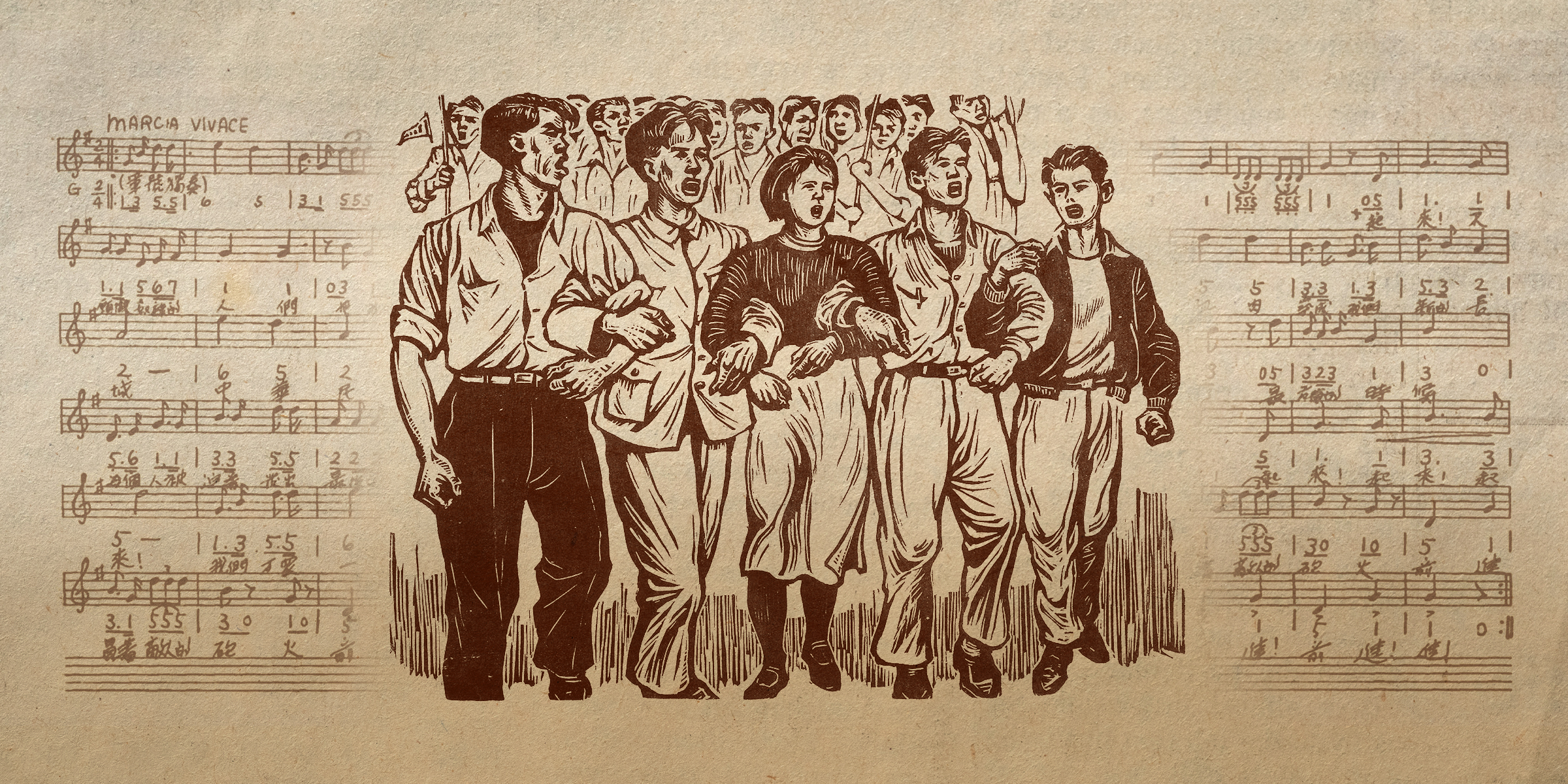

To mark 80 years since the end of what is officially remembered in China as the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, Sixth Tone revisits this cultural front: from a movie theme song that became the national anthem, to traditional woodcuts reimagined as protest art, and a cinema movement that aligned itself with national survival.

Together, they offer a glimpse into how, during one of the darkest chapters in modern Chinese history, art did more than endure. It fought back.