From Cinema to Tian’anmen: How China Got Its National Anthem

The history of China’s national anthem, “March of the Volunteers,” began on Sept. 18, 1931. On that day, Japanese troops faked an attack on a railway line in northeastern China — known as the Mukden Incident — and used it as a pretext to invade and occupy three provinces. By 1932, they had propped up the puppet state of Manchukuo, aiming to use the region as a springboard for their greater ambition of conquering all of China.

Despite this threat to China’s sovereignty, the Kuomintang, which ruled China while fighting a civil war against the Communist Party, decided on the policy of “pacify the interior first, then resist external threats.” It suppressed those who spoke up for national unity and resistance against the Japanese. Left-wing cultural groups that were affiliated with the communists, as well as the wider anti-Japanese national salvation movement, had to operate in secret and use fake identities.

Shanghai’s Diantong, for example, appeared like a regular company to the outside world. In reality, however, it stood under the direct leadership of the Communist Party. Situ Huimin, a Party member, had convinced the company, which originally supplied sound recording equipment to film studios, to move into making its own movies.

The production of Diantong’s first feature film, “Plunder of Peach and Plum” (1934), was a struggle. The crew, left-wing theater talents, lacked experience with the new medium of film, and shooting dragged on for far too long. The first rough cut left audiences unmoved, necessitating two months of costly reshoots, re-editing, and re-dubbing.

To recover financially, the company decided to speed up production of its second film, “Children of Troubled Times,” in which a poet whose friend died during a battle after the Mukden Incident decides to join the fight against the Japanese. A script, written initially by prominent cultural figure Tian Han, passed Kuomintang censorship, and filming began in January 1935.

That year, during the Spring Festival on Feb. 19, the Kuomintang authorities launched a mass arrest campaign in Shanghai. Tian was taken into custody in the early hours of the following day. Luckily, before his arrest, he had already completed the lyrics for the film’s theme song. The job to put them to music fell to 23-year-old composer Nie Er.

Once Nie landed the assignment, he set to work composing a melody in a small attic room on the third floor of a rented building on Avenue Joffre (now Huaihai Middle Road). In the dead of night, he would repeatedly sing through various possible arrangements: “Arise, those who refuse to be slaves …” The noise so angered his White Russian landlady that she threw him out. He moved in with the hospitable Situ, where his habit of starting every run-through with “Arise …” gradually earned him the nickname “Arise” from Situ’s mother.

Throughout the composition process, Nie made occasional adjustments. Tian’s original text was as follows:

Arise, those who refuse to be slaves!

With our flesh and blood, let us build a new Great Wall!

The nation of China has reached its most perilous moment.

From each one, the urgent call for action comes forth.

Us millions with but one heart,

Braving the enemy’s big cannons and airplanes, march on!

To make the melody flow more smoothly, Nie changed the last line of the lyrics from “big cannons and airplanes” to “artillery fire.” A more significant change, however, was replacing “The nation of China (zhongguo minzu) has reached its most perilous moment” with “The Chinese nation (zhonghua minzu) has reached its most perilous moment.”

Early in 1935, when composing the song “Farewell to Nanyang” for Tian’s play “Song of Renewal,” Nie had already made a similar adjustment. In that song, the male protagonist, returning from Southeast Asia to join the war of resistance, lamented the fall of Northeast China: “This concerns the life or death of the nation of China.” Nie changed “the nation of China” to “the Chinese nation.” This change — a difference of just one character in Chinese — implied China’s fate was also in the hands of the Chinese overseas diaspora.

One day in late March 1935, Nie arrived early at the Diantong studio and woke director Xu Xingzhi, who had just fallen asleep after filming through the night. Standing before the groggy director, he sang the freshly completed theme song. After hearing Xu’s suggestions, Nie made immediate adjustments. He gave the opening line a more rousing lift, and at the end, he introduced a bolder change: repeating the phrase “Braving the enemy’s artillery fire, march on!” and then shortening the final “march on” to a single “on.”

Compared with his earlier arrangement, which merely inverted the stresses on the three “march on” lines, this was a stroke of brilliance. Not only did the song now have a sonorous, driving rhythm and an ending that landed with force, but it also had a stronger sense of pressing forward to fight the enemy to the bitter end.

And so, the “March of the Volunteers” was born. Given that the Kuomintang authorities were using every means at their disposal to suppress the anti-Japanese national salvation movement, the song could only express its call to resistance in a roundabout and limited way; it could not openly shout slogans like “Down with the Japanese invaders!” In the specific historical climate of the time, the song’s terse and resolute words directly summoned “those who refuse to be slaves” to rise up and fight hand to hand, proclaimed clearly that the Chinese nation faced “their most perilous hour,” and urged them to “press on amid enemy artillery fire.” In doing so, it both skirted the censorship of the day and gave voice to the unspoken cry in many Chinese hearts.

“The March of the Volunteers” spread quickly, getting airplay on radio stations as a popular war song. With its stirring melody and lyrics, soldiers would sing the song as they marched into battle.

In 1949, with the Japanese and the Kuomintang defeated, the Communist Party decided on “March of the Volunteers” as its provisional national anthem. On Oct. 1, the day the People’s Republic of China was declared, “March of the Volunteers” rang through Tian’anmen Square.

Translator: Dasha Cowley; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

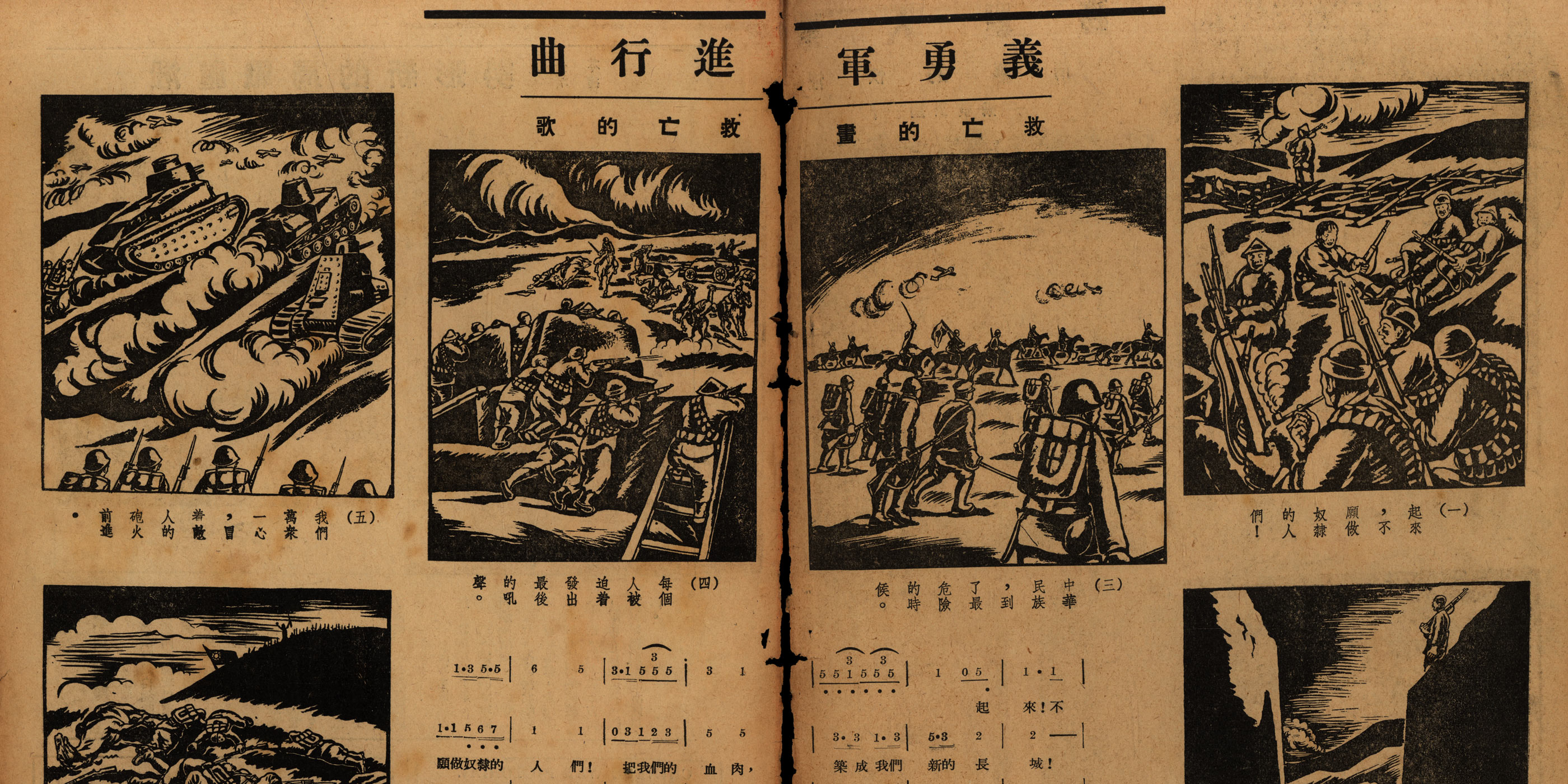

(Header image: Illustrations accompanying the lyrics to “March of the Volunteers.” Courtesy of the Shanghai Museum)