Towering History: A Photographer’s Fresh Take on China’s Pagodas

As of July, black-and-white specters of the past have been looming large in the Dunhuang Contemporary Art Museum, in Shanghai: the many pagodas of China, courtesy of a dedicated photography series by Fujian province-native Lin Shu.

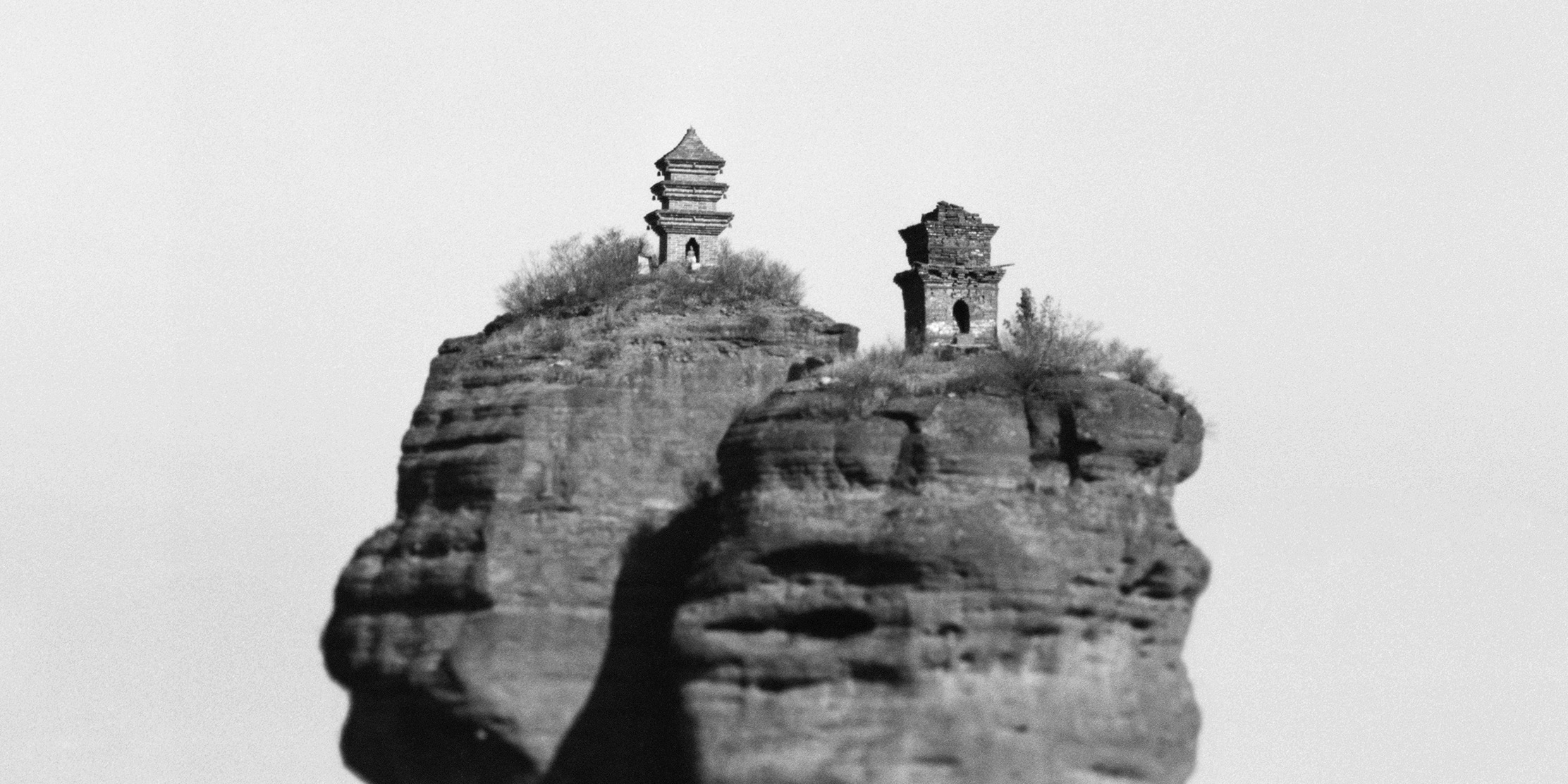

The exhibit, “Ta: Higher Heights,” showcases Lin’s photographs of pagodas in their many forms, capturing the tower’s near-ubiquity across the country. Standouts include a sharply tilting stone pagoda that evokes the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the bifurcated ruins of a brick pagoda cleaved right down the middle, and an ancient stone pagoda enveloped in bamboo scaffolding.

“Pagodas are quite extraordinary,” Lin tells Sixth Tone. “You see them everywhere in China, to the point that you might take them for granted. Yet when you look closer, you’ll feel a sense of ambiguity and mystery.”

Since 2017, after an almost-spiritual encounter with a Beijing pagoda from atop an overpass, Lin has roamed the country to document these stoic structures. His quest has spanned almost every region in China, comprising over 300 structures, each chosen for its cultural significance or quiet magnetism.

To the 44-year-old photographer, these tiered towers transcend architecture and embody a spirituality and faith that echo his pursuit of photography’s unadorned truth. He tells Sixth Tone that there is a complex “alchemy” to the act of pointing a camera to create art, and that he is “hunting for whatever ghost hides inside that process.” Throughout his search, he has been drawn not just to the aesthetic, but also to the immediate impression and affinity for the liminal space between what is real and what is just beyond reach.

By exploring the pagoda’s many forms, Lin traces conversations between tradition and art and ruminates on the point at which religion meets craftsmanship — where history brushes against everyday experience. Sixth Tone spoke with the photographer to learn more about this journey.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: How did your pagoda project begin?

Lin: After moving to downtown Beijing in 2010, I felt creatively stymied by life changes. Unsure of what to photograph, I started exploring nearby ancient structures. During that time, I took an experimental photo of Beijing’s Linglong Pagoda using a 4x5 large-format camera, though I didn’t think much of it then.

Two or three years later, I saw that same pagoda again one evening from a distance while on the city’s West Third Ring Road. I thought it was remarkable. I began reconsidering pagodas and realized they were truly unique enough to be a separate project. I have been formally taking photos of them since 2016 or 2017, starting from the pagodas in Beijing.

Sixth Tone: What draws you to pagodas? How do you understand their relationship to you, and to the modern world?

Lin: Pagodas almost only exist in China and other regions rooted in Buddhist tradition. They represent history, religion, architecture, and folk culture.

Honestly, it’s hard to pin down why they fascinate me, but it’s related to my personality and background. I was born in Fujian province in eastern coastal China, and I grew up watching temple rituals and hearing tales of spirits, demons, and ghosts. I have been drawn to the mysterious, and so I want photography to go beyond documentation and imbue more personal experiences and metaphysical elements.

Pagodas still matter to this day. Apart from their history and architectural beauty, they show how tradition carries on across generations. People now often see them as tourist stops; however, their meaning and function are still alive to this day.

Sixth Tone: How do you choose which pagodas to photograph? Which ones have left you with a strong impression?

Lin: I used to reference an old blog by a historic building connoisseur surnamed Wang, which listed thousands of pagodas. I’ve followed leads and journeyed to the actual sites to photograph about 300-400 locations, skipping only those that were badly damaged.

The pagodas I remember most are often the ones that were hardest to shoot. Shanxi’s Wooden Pagoda, in Ying County, stunned me with its grandeur, but it was wedged in dense housing. After two attempts, I climbed onto someone’s rooftop to finally get the shot. Then there was Hongtong County’s Feihong Pagoda, also in Shanxi, which features the world’s tallest glazed stupa. My black-and-white film couldn’t capture the brilliance of the colored glazed tiles, so I scaled back and reframed it with the surroundings.

Another memorable shoot was one that came as a pleasant surprise in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, when I photographed the White Pagoda of Qingzhou. Standing completely alone in the grasslands, I had a perfectly clear view of it, like it was an empty stage.

I don’t have rigid criteria. Often, I make my choices based on the immediate feeling I get when I encounter a pagoda and its surroundings, like with Hangzhou’s National Water Museum of China. The structure is not a true pagoda, being made of concrete and glass, but its deliberate tower-like form and clean proportions earned its place in my lens. Ultimately, what matters isn’t the pagoda’s age, authenticity, or integrity, but whether it shows traces of a bygone era or retains its aesthetic value.

I’ve come to believe photography should stay rooted in the present tense. It isn’t just a tidy, pre-planned record. Each pagoda is a singular object parked in a singular place. Some contexts dilute it, others amplify it. If the setting feels right — if it nudges the tower toward a pre-industrial quiet — I keep it in the frame.

Sixth Tone: Your pagoda series features many blurred scenes, not unlike blending in Chinese ink paintings. Why did you choose this aesthetic style over a more typological approach, like that of Bernd and Hilla Becher?

Lin: At first, I hadn’t settled on this visual style. I experimented using color, black and white, and sharper focus. Ultimately, the visual complexity achieved with a large-format tilt-shift lens and black-and-white film resonated with me and set the project’s tone. On a practical level, the out-of-focus parts also helped to minimize distracting background elements and focus the viewer’s attention.

It’s easy for photographers to associate my work with the Becher’s, given how we have focused on one type of subject. But I didn’t go the typology route. My work isn’t driven by academic critique or theory, nor do I consider criticism. I’m driven by my intuitive connection to the subject itself.

Sixth Tone: After capturing pagodas all over the country, what do you think of current preservation efforts in China?

Lin: Most pagodas I encounter, even the dilapidated ones, are technically under protection. The core issue isn’t about whether or not to restore them, but how well it’s done. Many recent projects prioritize structural soundness over authenticity, with crude results. In the eastern province of Anhui, for instance, several pagodas were plastered over with cement to approximate the shape of a pagoda, entirely losing all original form.

There are some pagodas I will never have the chance to photograph, which is a shame, such as the twin pagodas in Beijing’s Qingshou Temple. The pagodas were demolished during the 1950s due to urban planning efforts. Back then, the architect Liang Sicheng had proposed a preservation plan, which would have created a public park for the pagodas, but in the end, it didn’t come to fruition. Today, we can only imagine how visually striking these twin structures would have been in modern downtown Beijing. It’s truly a pity.

Sixth Tone: How has your understanding of pagodas evolved? At what point would you consider the project complete?

Lin: Initially, I viewed pagodas simply as Buddhist structures. But through my research and work, I discovered their remarkable integration into Chinese culture. While they originated from Indian Buddhist structures, they gradually integrated more Confucian, Daoist, and feng shui elements. Today, many pagodas function as feng shui towers (structures to regulate environmental qi) rather than religious sites. Yet their continued presence reflects an enduring folk cultural practice.

This is my longest-running project. With only Xizang, Xinjiang, and Hainan left to photograph, I’m just about ready to call it complete.

Editors: Hannah Lund and Ding Yining.