In China’s Brain-Computer Clinics, a Long Wait for a Second Chance

Every Wednesday morning, more than 20 patients, or their anxious family members, crowd into Dr. Yang Yi’s clinic at Beijing’s Tiantan Hospital.

By noon, the chief neurosurgeon at the country’s first brain-computer interface consultation clinic will have seen them all, often working through lunch. The hardest part, she says, is giving almost every one of them the same answer: “Not yet.”

Of the more than 800 patients who have come to her for assessment since the clinic opened for trials in March, only one has gone on to receive a brain implant.

“For now, selecting participants is like selecting astronauts,” she tells Sixth Tone.

Yang’s clinic is one of at least 14 that have opened since March, as major Chinese hospitals move brain-computer interface (BCI) research out of labs and into early clinical trials.

The rollout, concentrated in cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Wuhan, marks one of the fastest transitions of an experimental neurotechnology into hospital practice anywhere in the world.

Though still experimental, early BCI trials in China have produced high-profile breakthroughs: a paralyzed patient grasping a cup, an ALS patient speaking through thought, another taking steps with an exoskeleton.

The successes have fueled what domestic media call a “pivotal moment” for the technology’s entry into clinical practice.

“When the technology took off, it felt like everyone ought to be able to benefit from it,” Yang says. “In the clinic, however, we mostly see people who simply can’t.”

For China’s estimated 3.74 million people with spinal cord injuries, nearly 15 million stroke survivors, and tens of thousands living with ALS, the clinics represent a sudden, if narrow, opening. Patients are traveling long distances to register their interest, hoping for what existing medicine cannot yet offer.

But most trials are small and restricted to patients who meet strict medical criteria. Yang explains that these criteria prioritize safety and ensure pilot trial funding is used effectively. That gap between expectation and reality has made public communication as critical as the trials themselves. Yang calls it “managing expectations.”

“I’m not afraid of telling patients, ‘Not yet,’” says Yang. “What I worry about is letting them believe that implanting a chip means they’ll stand up right away. Many come in with misunderstandings based on what they’ve seen online. We need a way to bring them back down to the reality of clinical medicine.”

Waiting game

Since a car accident in 2023 damaged his spinal cord, He — who asked to be identified only by his surname — has applied to every trial he can find. The answer is always the same “Not yet.”

The first time he saw the words brain-computer interface, he was sitting in a wheelchair in his hometown in the eastern province of Fujian, scrolling through the news on his phone.

The headlines described a future that seemed almost unreal: paralyzed patients moving robotic arms, standing, walking. Non-invasive BCIs, such as EEG caps, were already appearing in fields like education and VR gaming, and a handful of cases hinted at their potential in rehabilitation.

“When I first heard about it, I felt fired up with confidence,” says He, who’s in his 30s. By 2025, as hospitals across China announced new BCI clinics, he began sending applications across the country.

“Doctors told us there’s no cure for his condition,” Tan, He’s partner, who also asked to be identified only by her surname, tells Sixth Tone. “This is our only hope.”

He first applied to a U.S. program in 2024 but was disqualified because of his nationality. In 2025, as trials began opening in China, he learned that strict medical requirements also limited who could take part.

Most programs for paralyzed patients focused on upper-limb recovery, but He still had full arm function. Other programs targeted lower-limb recovery, but required some sensory feedback in the legs — which he had lost.

It was around this same time that Qiqi, who at the age of 27 became paralyzed when severe lupus damaged her spinal nerves in 2018, was introduced to the idea of a BCI trial by her doctor.

“I want to try it so badly. Even if the chance is one in 10,000, maybe I could walk again, maybe I could take control of my life again,” she says, asking to be identified only by her online username for privacy.

Each day, she scrolls through social media for trial announcements, but none lead anywhere. “It’s like searching for a needle in a haystack,” she says.

Confusion over how to join a trial is exactly what the new BCI clinics are meant to address, says Jiang Lei, chief neurosurgeon at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. In July, his hospital opened the first such clinic and dedicated ward in Northwest China.

“BCI research used to take place mostly in labs, with patient recruitment feeling like a one-way selection process, distant and disconnected,” says Jiang. “These new consultation clinics work more like patient-centered forums, where doctors can meet people face to face and listen to their most urgent concerns and questions.”

Tiantan’s team began BCI research in 2021, working with patients whose paralysis and consciousness disorders no longer improved through conventional therapy. BCI, she says, felt like “a beam of new light — faint, but far-reaching.”

In 2022, she launched a social media account to explain trial requirements and counter viral exaggerations. On Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, she posts daily under the name Tiantan Consciousness Disorders Doctor Yang Yi, to over 36,000 followers.

Most clips are shot in her clinic, answering patient questions: Can brain-computer interfaces do it all? Why must BCI trials take place within two years of hemiplegia? What comes after meeting recruitment criteria?

She later expanded to the lifestyle platform Xiaohongshu, known in English as RedNote. Her comment sections are filled with anxious messages — cases of brain bleeding, stroke, paralysis. She has little time to reply, but often likes comments, almost as if to say, “I see you.”

Criteria cage

Much of the frustration across China’s new BCI clinics stems from strict eligibility criteria.

At Tiantan, for instance, trials are limited to stroke survivors with hemiplegia or paraplegia, typically young to middle‑aged, within two years of onset, and with motor cortex function intact.

The criteria, designed as much for patient safety as for the limits of the technology itself, immediately rule out most patients, including He and Qiqi.

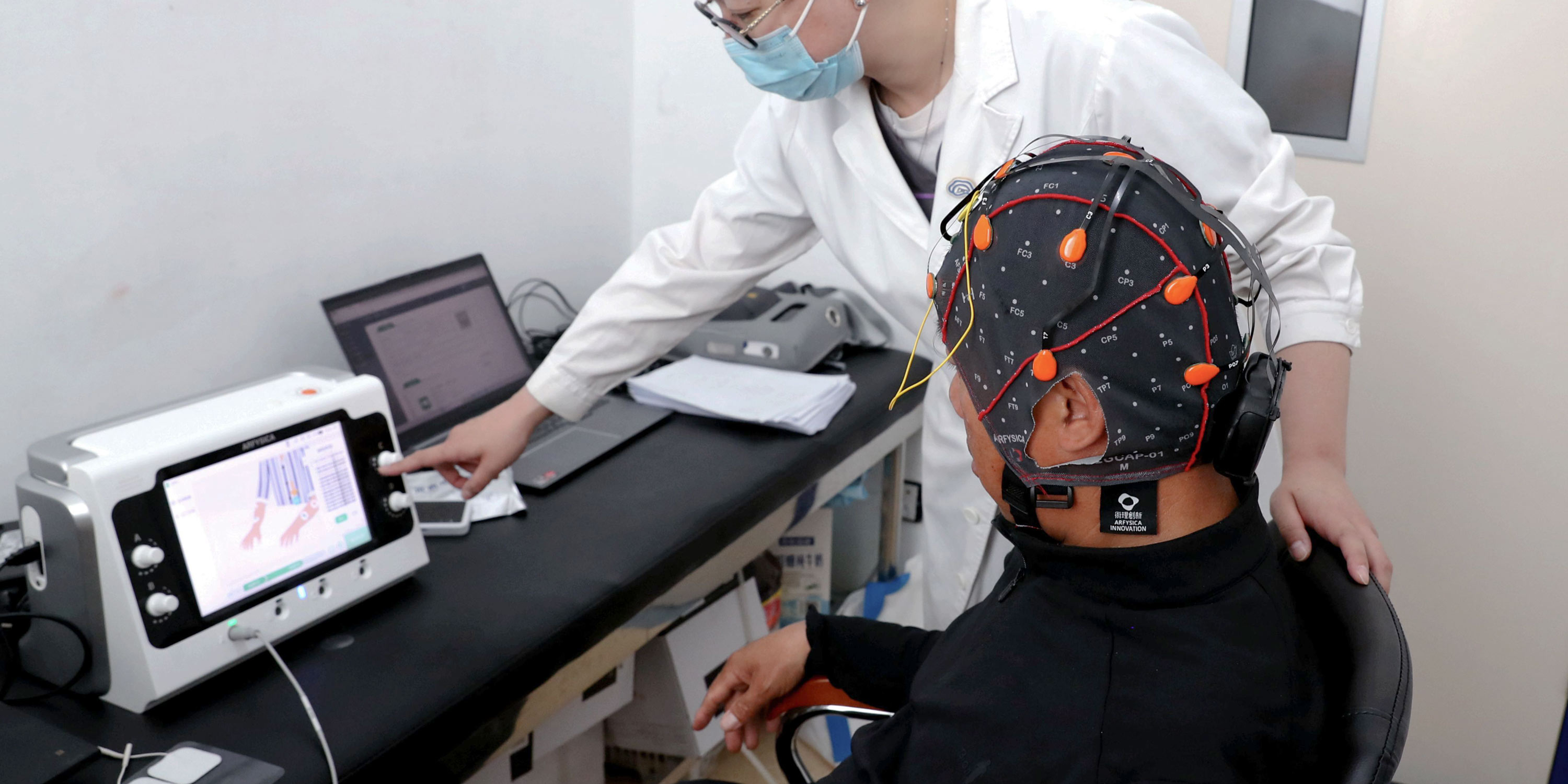

Selection at Tiantan starts with clinical screening, then EEG signal tests, followed by a decoding assessment in the lab. So far, only a handful of patients have cleared every stage.

The harder part, Yang underscores, is teaching the brain to communicate in a language the machine can understand. Human thoughts are messy; signals drift and disrupt easily.

“BCI isn’t plug and play,” says Yang. “Patients need extreme focus and must train their brains to deliver clear, machine-readable intent. That takes weeks or even months of preparation.”

Neurosurgeon Jiang takes the same view: “For patients not eligible yet, we’re simply waiting for a safer moment.”

Until then, He and his partner Tan have agreed to take things in stride. Though He has yet to pass an initial screening, he says: “We’ll just focus on living our life.” The couple met while traveling and still travel — wheelchair in tow — supporting themselves through freelance work.

Months of using a wheelchair have strengthened He’s upper body; he now transfers in and out of cars independently. When reached in July, he was driving toward the Xizang Autonomous Region with a modified steering handle.

Qiqi has begun working as an online customer service agent, hoping to build a following as a social media influencer.

Her family had exhausted most of their savings on her lupus treatment. Now, nearly all her earnings go toward saving for a trip to Jiang’s clinic in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region — a journey that can take more than 11 hours on a train from her home in Kashgar. Reaching Yang’s clinic in Beijing would take even longer and cost considerably more.

For the moment, Yang and Jiang say they’re trying to close the gap with telemedicine systems that could bring consultations and follow‑ups to patients in remote areas.

Speed of thought

Around them, China’s wider BCI ecosystem is moving fast.

Since early 2025, Beijing and Shanghai have rolled out promotion plans. National regulators have accelerated device approvals. Central China’s Hubei province has published the first price guidelines: 6,552 yuan ($910) for invasive implantation, 3,139 yuan for removal, and 966 yuan for non-invasive fitting.

By 2040, China’s BCI market is projected to exceed 120 billion yuan ($16.5 billion).

“After a decade of foundational research, we’re entering a golden window of opportunity,” said Wang Shouyan, director of Fudan University’s Research Center for Nerve Stimulation and Brain-Computer Interfaces, in Shanghai.

“Every breakthrough has the power to reshape a life. But with millions of patients still waiting, I can’t help but ask: how do we honor every cent and make sure that hope isn’t wasted?”

Inside the clinics themselves, each new trial feeds the growing dataset that will shape how BCI is scaled in the years ahead.

“It’s like establishing real‑world training grounds across the country,” says Jiang. “By gathering these experiences, we can create unified and safer treatment standards, helping the entire field avoid detours, and ultimately allowing more patients to benefit.”

Still, the move from trials to treatment will depend on breakthroughs in the technology itself. At the core are electrode chips — the tiny sensors that read brain signals. For BCIs to become reliable in daily use, these chips will need to improve in sensitivity, accuracy, and how long they can function inside the body without degrading, according to Yang.

The decoding side has its limits too. Current BCIs can only interpret brain activity linked to very specific mental tasks. They can’t pick up free‑flowing thoughts. Instead, they detect only the intentions they’ve been trained to recognize in advance.

At Shanghai’s Jiao Tong University, a third‑year Ph.D. student is working to decode the rhythm of hand movements, expanding on earlier studies that could only tell left from right.

He admits to frustration with the limits of current technology and the scarcity of usable data. “It feels like I’m helpless in front of 99% of the real questions,” he says, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“There’s such a disconnect between what I’m actually working on and what people imagine that I’ve given up trying to explain. I just tell them I study computer science. Or AI.”

The visions that dominate public imagination — reading thought or memory transfers — remain far beyond today’s technical framework.

For He, the goal is far more basic.

“What I want most is to manage my bladder and bowels again,” he says. “It’s a matter of dignity, and it greatly affects how independent I can be.”

He uses a urine drainage bag and spends months trying to train his body into a routine. But accidents still happen.

Every time they go out, Tan carries a spare pair of pants in her bag. When she isn’t there to help, He often grips his urine bag with his teeth so he can free his hands to move his body.

The physical toll is just as serious. Urinary tract infections are common, and in severe cases, can lead to kidney failure. According to official data, patients with spinal cord injuries experience an average of 10 urinary complications per year.

In May, a trial patient in Beijing showed promising results: after two weeks of BCI training, he reported improved bladder and bowel control, as well as stronger muscle activity in his upper legs.

For patients like He, even small gains like this carry the weight of possibility.

Back at Tiantan, patients deemed ineligible for trials are kept on a watch list, revisited each time a trial opens or a new device is cleared.

“The technology will catch up,” Yang reminds those waiting. “The best thing you can do is be ready for it.”

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Dr. Yang Yi conducts an EEG test on a patient at Tiantan Hospital. From Beijing Tiantan Hospital)