Decoding the Chinese Computer

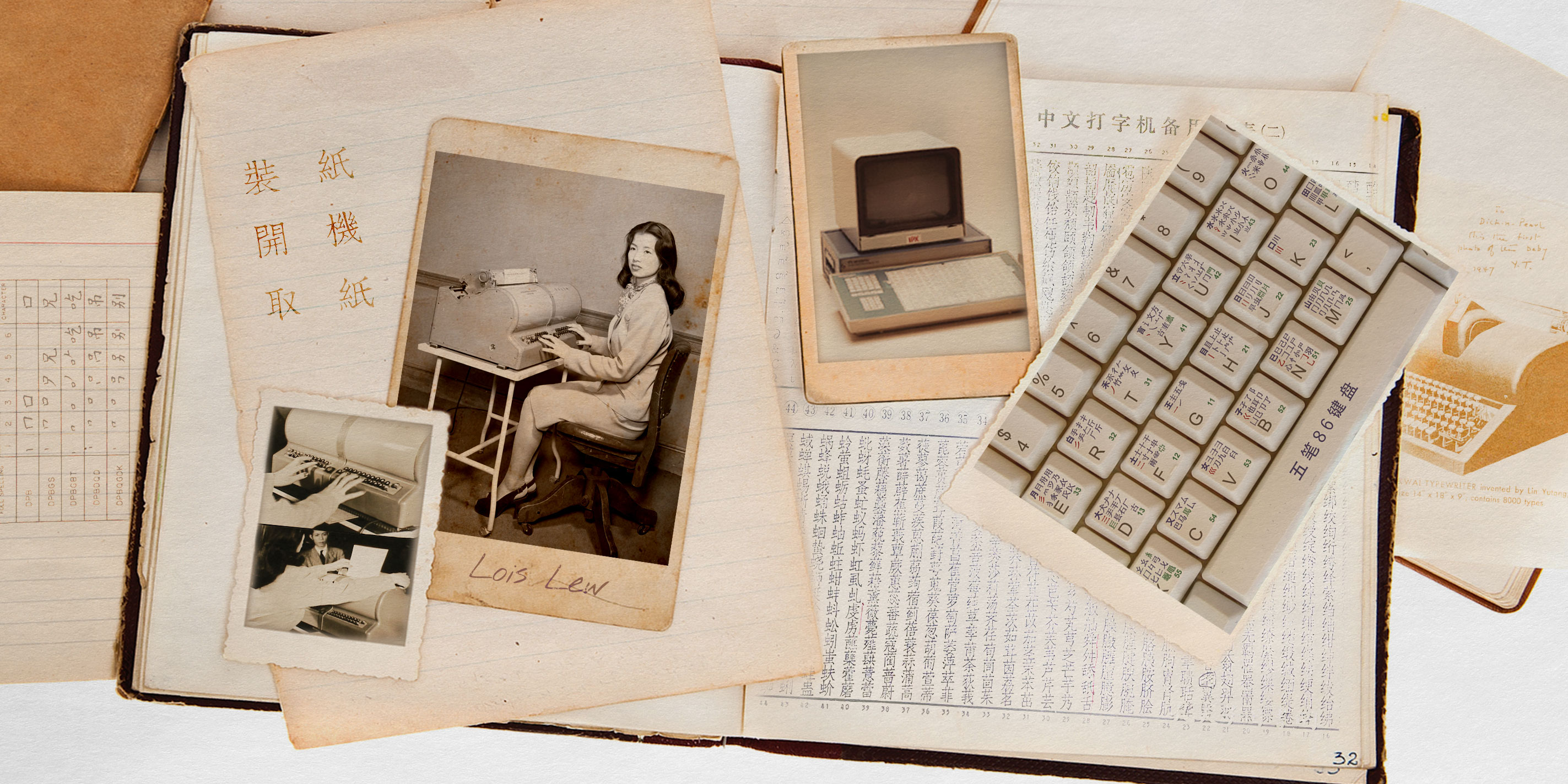

In 2014, Stanford historian Thomas Mullaney placed a call he had been waiting to make for a decade. The woman who picked up, Lois Lew, was a Chinese-American who had spent most of her life running a restaurant in upstate New York. Few knew that, in her youth, she had played a key role in demonstrating the feasibility of an invention once thought impossible: an electric Chinese typewriter.

As the first-ever professional Chinese input operator, Lew was tasked with showing off Chung-chin Kao’s innovative Chinese typewriter system to roomfuls of skeptical journalists and investors in the 1940s. Although Kao’s complex machine failed to catch on, Lew’s presentations were a success: She proved that the device could be mastered — and by extension, that one of the world’s most ancient scripts could be brought into the age of electromatic automation.

Lew passed away in 2023, but her story would form the basis for a crucial chapter in Mullaney’s 2024 book, “The Chinese Computer,” which explores the global effort to digitize Chinese characters. It was a problem that drew in engineers, linguists, and entrepreneurs from around the world — but also, as Mullaney points out, ordinary men and women like Lew.

In the process, Mullaney meticulously documents how diverse figures like MIT’s Samuel Caldwell — who had no professional background in the Chinese language — and Silicon Valley engineer Chan-hui Yeh became captivated by the challenge of Chinese computing, often through chance encounters that redirected their entire careers.

Through these interconnected stories, Mullaney elevates a footnote in computing history into a powerful examination of how the “universality” promised by technologists has always been culturally specific. In the process, “The Chinese Computer” highlights how the challenge of representing thousands of characters in computational form — once dismissed as needlessly complicated, if not outright impossible — led to innovative features we now take for granted, from predictive text to prompt engineering.

But Mullaney’s book is also a story of loss — an idea that Mullaney, who founded the Stanford Initiative on Language Inclusion and Conservation in Old and New Media (SILICON), has been obsessed with since he arrived at Stanford 18 years ago, and is the subject of his forthcoming work, “How We Disappear.” It’s not just stories like Lew’s that are in danger of vanishing: “The Chinese Computer” is very much a story about how new technologies can accelerate the process of loss, as difficult or complex characters fade away because they are not supported by an input tool or are crowded out by competing variants.

Last year, I spoke with Professor Mullaney over Zoom about “The Chinese Computer,” the chance encounters that created it, and the importance of stories like Lew’s to history. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Afra Wang: When reading your book, I was struck by the variety of research projects that were undertaken to build, improve, and diversify Chinese computing. You had IBM, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, MIT, and even the CIA all working on the issue. However, what truly captured my imagination were two characters you introduce in the first chapter: Chung-chin Kao and Lois Lew. What’s the significance of these figures to your research?

Thomas Mullaney: Lois Lew almost didn’t make it into the book. She’s on the cover of “The Chinese Computer,” but her chapter — the one about IBM’s electric Chinese typewriter — almost ended up in my book on the Chinese typewriter, published years before I had a chance to finally speak with her.

On the face of it, it’s a story about a Chinese typewriter invented by Kao and then developed into a prototype by IBM. But the device is electric — it’s an electro-automatic system and it has a keyboard. And the keyboard is using special kinds of code to make Chinese. So it was tough to decide which book to put it in: the one about Chinese typewriters, or the one about Chinese computers. One thing led to another, and I ultimately decided not to include it in “The Chinese Typewriter,” which delayed its publication for nearly seven years.

And in that time, I finally got to meet Lois over the phone. I consider that to be a wonderful accident. If I had written about her or the IBM machine and then spoken with her 10 years after the book’s publication, there would have been nothing I could do, except perhaps write a follow-up article. But I think more than anyone in the book, Lois Lew humanizes the entire story, because at that moment in time, she and Grace Tong at IBM were some of the only Chinese inputters in the entire world.

After Kao invented prototypes of his machine, he faced widespread suspicion and doubt about whether it could ever work. The pressure to prove its viability fell not on his shoulders, but on Lew, as the presenter. Hired by Kao for trade tours in the United States and China, she would sit before auditoriums filled with hundreds of people — journalists, statesmen, diplomats, businesspeople. Her task was to demonstrate that a human being could wield code of this complexity in real time.

Her life was tumultuous and fascinating in its own right. Her family, like many others, was torn apart by the outbreak of the Second World War. She was a refugee. As a young adult, her parents arranged a marriage to someone she’d never met in the United States. She traveled by herself, didn’t speak a word of English, and arrived in a world that couldn’t have been further from her home. Then she became effectively the face of this venture by IBM and by Kao.

It’s one of those exceedingly rare opportunities as a historian where the actual empirical facts and the narrative are consonant with one another. You don’t have to dramatize it because it is so acute already.

Wang: While the title suggests the book is about the history of the Chinese computer, the “Chinese” element is actually a global story. Could you walk us through the key archives and primary sources that shaped your research? I’m curious about the challenges you faced accessing institutional records, and how you navigated these obstacles to piece together this history.

Mullaney: This is not a story of Chinese engineers or engineers of Chinese descent that were waging a very clear and obvious kind of technological struggle against the West. The Chinese computer as a concept and practice is a global problem that attracts engineers and entrepreneurs from Europe, the United States, the Soviet Union, Japan, and, of course, the Chinese-speaking world.

There are many figures in the story for whom the work is, in some sense, a natural progression in their life or career. But there are others who, although they have the chops — the bona fides to be able to think through these systems — there is nothing about their trajectory in life that says, “Guess what they do tomorrow? They dive into the realm of Chinese computing.”

Consider Chan-hui Yeh, the Taiwan-born American engineer I write about in Chapter 3. Yeh spent most of his career optimizing manufacturing plants and quality control systems. He built a successful career at IBM but ultimately quit to pursue Chinese information technology — despite having no prior professional experience with Chinese language technologies.

Similarly unexpected is Samuel Caldwell from MIT. He was a student of Vannevar Bush, a giant in the academic-military-industrial universe. But Caldwell didn’t speak or read a word of Chinese.

In both cases, something happened in their lives that planted a little seed in their mind that began to blossom.

Yeh, by his own account, recalled being a student at the Virginia Military Institute and listening to a lecture by Arnold Toynbee in 1958 about the “coming collapse of China,” brought about by its language problem: If China were to change to a Latin alphabet, the glue that had kept Chinese civilization together for centuries and millennia — that is, the Chinese character — would be threatened. With characters, a Cantonese speaker and a Mandarin speaker could share a common written form, but if that glue cracked and crumbled, China would collapse. Something about that stuck with Yeh. He did not immediately try to start building a Chinese computer. He finished his degree. He got a job with IBM. But it just kept gnawing at him to the point where he committed himself in the late ’60s. (Yeh’s company would release the IPX, a computational typesetting and transmission system for Chinese, in the 1970s.)

As for Samuel Caldwell, by all accounts his involvement came about because of dinnertime conversations between Caldwell, his wife, and overseas Chinese students studying at MIT. They’d talk about little things like, “Where are you from? How do Chinese characters really work?” One student who went on to work with him made a passing comment that shocked Caldwell. It was something to the effect of, “There are no letters in Chinese. But Chinese characters do have a ‘spelling.’”

The student was referring to stroke order — the order in which characters are written. Something clicked for Caldwell in that moment. “Wait a minute,” he thought. There’s a set way to do this, one that’s susceptible to the architecture of a logical circuit. And his whole life changed direction. Although he didn’t quit MIT — it wasn’t as dramatic as Yeh — he completely shifted his focus and became obsessed with this puzzle. Despite his early death, all signs suggest he would have devoted much of his life to this question.

In other words, the puzzle of modern Chinese information technology captured the imaginations of people worldwide. As a result, the source materials are scattered across the globe. You’ll find them in small, beautiful museums, at the Cable and Wireless Corporation archives in the U.K., and in people’s basements and attics.

This wide dispersion is why it took so long to write. A major component was oral histories — tracking down the sons, daughters, and grandchildren of key figures. I would cold call them, saying, “I’m sorry to interrupt, my name is Thomas Mullaney, and I’m working on this project. Would you mind speaking with me?” The response rate was remarkable — better than 99 out of 100.

Wang: A lot of your career has been exploring the intersection of technology and linguistics. What initially sparked your fascination with this topic? Was there a particular moment or realization — an “aha” moment — that crystallized your idea to pursue this line of research?

Mullaney: I’ve been at Stanford for 18 years now, and I walked in the door with an obsession. It had nothing to do with my dissertation and first book, nor with what would eventually be published as “The Chinese Typewriter.” My obsession was with disappearance, ruin, entropy, obsolescence, degradation, rust, rot — anything and everything about how it all comes apart. But I didn’t know what to do with this concern or these questions. I didn’t know how to give them shape, because entropy is everywhere and always, making it difficult to contain within clear boundaries.

So I secured some funding and created a speaker series at Stanford called Project Absentia. It was really fun. I invited scholars from various disciplines to give lectures on disappearance from their perspectives: a leading linguist discussed language death, a prominent historian of ideas explored the concept of death, and an expert addressed species extinction through the lens of conservation biology. The prompt was essentially: “What does disappearance mean in your field?” I served as the moderator and organizer, alongside a graduate student assistant who’s now a professor at Princeton. We were the only constant throughout the series.

The speakers never crossed paths, since they were arriving and departing at different times. It fell to me to give a summary of the whole experience in the final talk. I had to write a paper — it was literally called “How Everything Disappears.”

It wasn’t intended to be grandiose or pretentious. One of the key concepts we had been working with, which I was trying to crystallize for myself, was that disappearance begins at the moment of production. Things start vanishing the instant they’re created. It’s not just active destruction like book burning that makes things disappear — the very act of production itself can be a site of disappearance. This concept had emerged in many different talks, and I wanted to give it concrete form. For my case study, I examined how Chinese characters disappear, specifically focusing on those characters that are now considered “hard to understand” — ones whose pronunciation and meaning have been lost to time.

These characters exist in a liminal state — they’re both present and absent simultaneously. I discovered a fascinating dictionary of difficult characters, essentially a compendium of Chinese characters that inhabit this paradoxical space. How does this happen? Was it due to imperial taboos? Were they banned? The answer, surprisingly, is generally “No.” These characters simply drifted out of usage until their meaning was forgotten. It wasn’t a deliberate act like the burning of Mayan texts — it was a gradual fading away. The challenge was to explain this drift: how a character slowly fades from use and eventually becomes non-existent.

One key point in this timeline involves moments of technological production — specifically, the ability to mass-produce texts. When you can mass-produce texts, the form of the character included in that machine becomes crucial. Let’s say that until a certain point in history, you could mass-produce text at a rate of x characters per minute. But what happens when you can suddenly produce 10,000 characters per minute? The characters in that machine — their specific form — will quickly become the dominant type, crowding out all other characters that might exist in books on shelves.

Through environmental change alone, these alternative forms will become increasingly rare over time. I started thinking about simplified characters, different writing forms, and how various Chinese regimes dealt with character variants. I considered movable type — that was important. Then I thought about typewriters and wondered, “Wait, was there a Chinese typewriter?” That was the moment everything clicked.

I started wondering whether this had been done before. I tried to figure out if anyone had worked on this topic already. At that time, the best existing work was an honors thesis by an undergraduate student at Cornell, whom I cite in my book — but beyond that, nothing had been done.

So I found myself in this crucial space where research begins. It’s that moment of simultaneous clarity about what you want to do, paired with a complete lack of clarity about why this particular thing matters.

Wang: Your work, not just in this book, but also in “The Chinese Typewriter,” pays considerable attention to illustrating the role of female labor in the development of Chinese information technology, from “typewriter girls” to “input method editors” (IME) such as Lois Lew. The contributions of women to the early days of computing were long overlooked, and historians are now addressing this oversight by digging into figures like programmer Grace Hopper and 19th-century polymath Ada Lovelace. How does gender play into the story you tell in “The Chinese Computer”?

Mullaney: That’s a big one.

One surprising finding from my work is that while the gender dimensions of Chinese language technology parallel those in other language environments, they don’t completely align. When examining the actual records of typing schools and institutions, about 30% to 40% of students learning to use Chinese typewriters were men. But these male typists essentially vanished from history because there was no cultural trope of the “typewriter boy.” This reflects how Chinese information technology history, while developing its own unique pathways, remained embedded within a Western-dominated technological narrative. The “typewriter girl” archetype persisted because it was the established Western model.

In reality, Chinese typewriting demographics remained diverse well into the 1950s. It wasn’t until the era of personal computing that clerical labor became more decisively feminized, following classical historical patterns. For instance, footage of the Ideographix IPX machine in Taiwan shows primarily young female operators, though some men are present. This illustrates the staggered nature of this history, with its own distinct turning points and timelines.

There are several prominent figures worth noting, particularly Jenny Chuang at Wang Labs. Although I only briefly sketch her story in the book, she stands out as an extraordinary person.

Chuang was a prodigy in engineering and computing even before Wang Labs on the East Coast attempted to become the “IBM of China.” In fact, she had already been tasked with programming the operating system for Wang Labs’ electric word processor. This flagship product was groundbreaking — and Jenny Chuang may have been one of the only women leading operating system development at the time.

While I’m not a gender historian and don’t claim to be, I believe gender historians have hit on an important truth: It’s not enough to simply find notable, brilliant women, write hagiographic biographies of them, and call it equity. Finding Ada Lovelace, Grace Hopper, or the brilliant mathematicians who got us to the moon doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods.

In my way of thinking — and this isn’t original to me — I’m far more fascinated with figures like Lois Lew who don’t hold a Ph.D. or speak multiple languages. They aren’t prodigies or hidden geniuses in any conventional sense. Lois Lew was simply a middle school-educated, dynamic, amazing young person. She’s not another Ada Lovelace rediscovery, nor does she need to be. Many would agree that we can’t overcome the long-dominant celebration of male innovators and inventors by simply writing equally unproblematic biographical treatments of prominent women and declaring equity. The real shift, which has been happening for decades, is understanding that none of these systems exist as singularities at all.

The story of Lois Lew truly matters for both history and this book. While Kao was the inventor and engineer — it was his brainchild — Lew was the one who had to learn to use it. She had to embody it and form a relationship with the technology. She represents the human element in the human-machine interaction, literally embodying that relationship.

This kind of learning process is difficult to articulate — much like explaining how to ride a bike. It involves deep, nonverbal, non-linguistic processes. When I asked Lois how she memorized everything, she couldn’t break it down into simple steps or tricks. While this learning process is lost to history, it remains a fundamental part of technological development. Despite IBM executives’ and Mergenthaler’s skepticism, Lew proved it could be done. She demonstrated her skills in front of hundreds of journalists, engineers, and diplomats. As they witnessed this remarkable form of human-machine interaction, their reaction was one of genuine disbelief — not just the common expression, but literal incredulity.

I see it, but I still can’t quite believe it. It will take time — later in the story — for belief systems to catch up with the empirical reality. The fact is, it’s now possible for an ordinary person, not just a polymath, to live with this bizarre form of real-time code as part of everyday life. More than half of the global population already does this through their interaction with digital objects. That’s where — well, to the extent that the book has something to offer scholars of gender and technology, this might be part of its contribution.

Wang: You’ve spoken about “weird options” that arose out of a need to retrofit new tech onto old writing systems. There’s a Chinese input method called Wubi (Editor’s note: Short for Wubizixing, literally “five-stroke character model input method”) developed in the 1980s, which uses only stroke components instead of pronunciations to input Chinese characters. My dad learned Wubi as a child. It is incredibly fast, and I couldn’t beat his speed. But Wubi is gradually disappearing …

Mullaney: No, you couldn’t beat your dad’s speed because the maximum input potential and efficiency of the Wubi method are higher.

The Western-dominated technological world forced half of humankind to be “weird.” You wouldn’t wish it upon your enemy. It’s not a blessing — it’s a terrible condition. But out of that, things evolved. Over the course of a century and a half of being forced into this position, changes occurred. Adaptations were made, experiments were tried, sacred things were questioned, and traditions were challenged. So it’s no coincidence that after a century and a half, all that “weirdness” is starting to show its value, and Silicon Valley is asking, “How do we get some of that? Why can’t we have Alipay?”

But these innovations didn’t appear out of nowhere. It’s not just a technical problem. Sure, you could program similar apps, but who would use them? This isn’t about hardware limitations anymore.

There’s always this idea of a default “normal” human-computer interaction. But keep in mind that for more than half of global computing users worldwide, there has never been — and could never be — a default, normal solution. Put simply, the willingness to embrace new technology is much higher in the Chinese-speaking world than in the English-speaking world.

This will be fascinating to watch in VR and AR development. While you can miniaturize almost anything, you can’t shrink the QWERTY keyboard effectively. I’m certain we’ll see English-speaking VR users typing on virtual QWERTY keyboards — that’s how absurd it will be. Haptic gestures won’t make a difference. We only use gestures in specific contexts, like with remote controls or in cars. The English-speaking world isn’t ready to wholly embrace a new input paradigm. This resistance isn’t due to technical limitations or the lack of systems. The technology exists — it’s the cultural adaptation that’s missing.

Editor: Cai Yineng.

(Header image: Lois Lew and various generations of Chinese typing systems. Visuals from Thomas Mullaney, VCG, and public domain, reedited by Sixth Tone)