What’s the Right Way to Translate Chinese Dish Names?

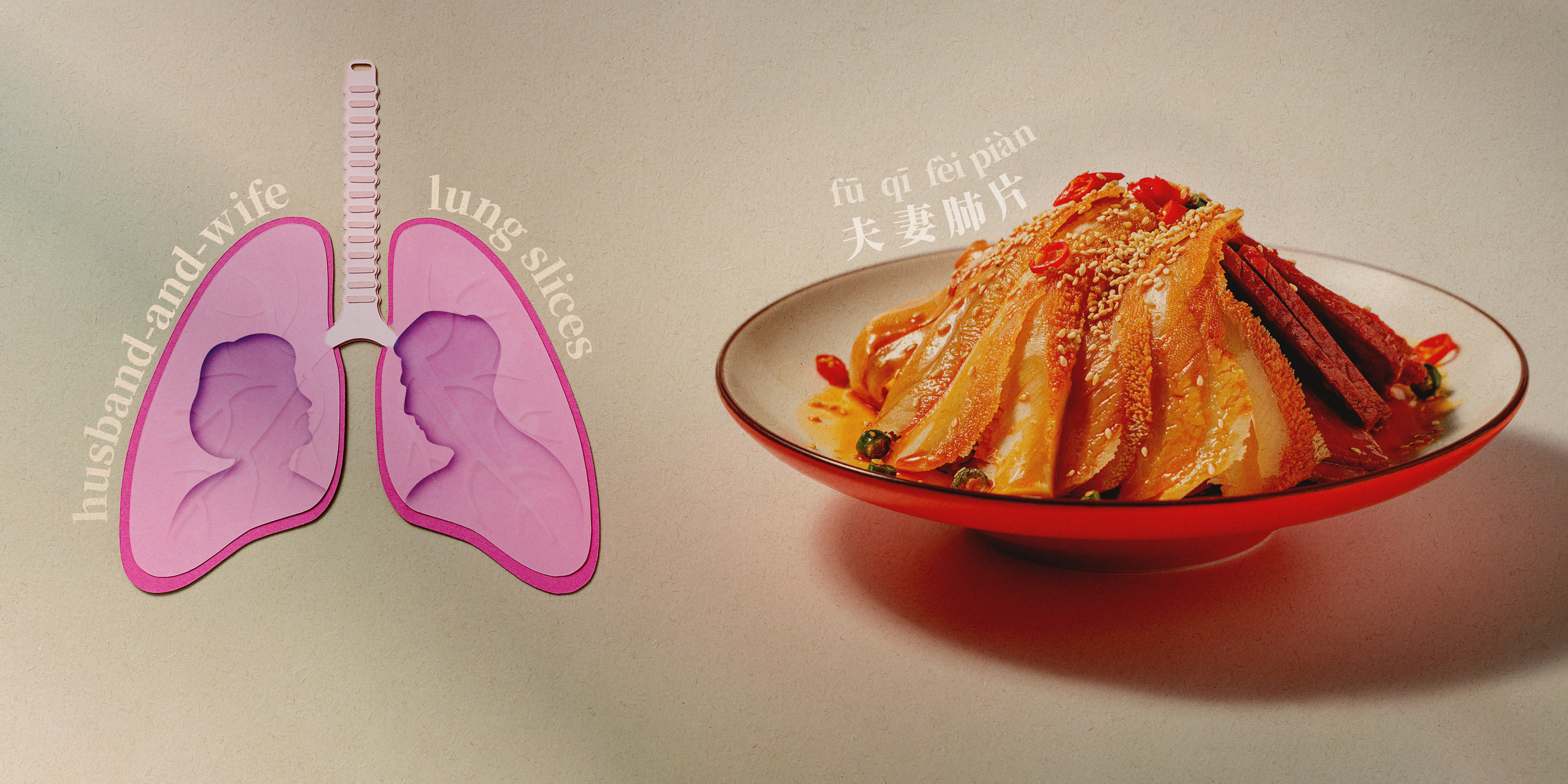

The translation of culturally specific Chinese terms has long been a challenge for even the best of experts, with culinary terms ranking among the most difficult. Not for nothing, a recent 2,000-word CNN article decried the “impossible task” of translating foods like fuqi feipian, a chilled dish of beef offal served in chili oil that literally means “husband-and-wife slices.”

But do these dishes need to be translated at all? While diners around the world have grown accustomed to ordering ramen or bibimbap, most Chinese restaurants continue to render their dishes in English. At an academic conference last year, I met a scholar who was advising the government of Quanzhou, in eastern China’s Fujian province, on how to translate local dish names into English as part of an international tourism push. Although I recommended using transliteration instead, they ultimately chose the more conventional approach of describing the dishes using their ingredients and cooking methods.

It’s an understandable choice. The descriptions help tourists better understand what a dish contains, making them more likely to try it. Many Chinese also worry that transliterations may not seem like a “real” translation — officials in particular sometimes believe that simply rendering Romanized names in pinyin looks unpolished or incomplete. But contrary to popular belief, transliterations may actually help non-Chinese diners better appreciate the cultural uniqueness of Chinese cuisine.

Historically, linguistic borrowing has always been the most common method for transmitting culturally specific terms across languages. This manifests in two primary ways: loanwords and transliteration. If the source and target languages share the same script, borrowing generally involves loanwords — e.g., English borrowing the word “espresso” from Italian. If the scripts differ, it involves transliteration — English gyoza from the Japanese.

Semantic translation, on the other hand, conveys meaning rather than form. Traditionally, it prioritizes fluency and naturalness in the target language, even if that means departing from the original wording — rendering the Chinese shizitou as “meatball,” for example. However, semantic translation can also mean literal translation, even if the result seems foreign or puzzling — such as translating shizitou as “lion’s head.”

I’ve been working on an ongoing project exploring how to render Chinese food names into English, with entries covering provinces across the country. Throughout this process, I’ve been struck by the challenges involved. Many translations end up being long, awkward, or difficult to read and remember. Hong Kong scholar Isaac Yue and British food writer Fuchsia Dunlop — both interviewed in the CNN article — express a similar sentiment: Chinese dishes are notoriously difficult to translate accurately, due to the country’s rich and layered culinary history, a cultural preference for vivid imagery, and the presence of ingredients and techniques that have no direct equivalents in English.

In the past, such efforts produced many overly literal translations that were widely criticized for being linguistically inept. Yet today, these translations are valued for preserving the cultural context and thought patterns of the Chinese original. Their perceived awkwardness can even convey a certain cross-cultural charm, sparking curiosity and engagement. This goes both ways: the English idiom “armed to the teeth” was once rendered stiffly into Chinese as wuzhuang dao yachi — a phrasing that, despite its initial oddity, has since gained popularity among Chinese speakers for its vivid imagery. Literal translations may seem unsophisticated, but they enrich the target language and culture, whereas overly polished translations risk erasing distinctive flavors.

Thus, translating fuqi feipian as “husband-and-wife lung slices,” yuxiang qiezi as “fish-fragrant eggplant,” fotiaoqiang as “Buddha jumping over the wall,” or shizitou as “lion’s head” may initially baffle English speakers, but could ultimately foster greater appreciation for the unique foodways they represent. Through such renderings, the cultural depth of Chinese cuisine may gradually enter global consciousness, while broadening the linguistic and cultural horizons of the English language.

By assuming that transliteration or literal translation will only confuse audiences, we underestimate the transformative power of translation. Opting only for idiomatic, instantly comprehensible translations may facilitate communication but forfeits the chance to showcase cultural richness. In the end, translation is not merely a utilitarian tool for surface-level communication. It operates at a deeper level, subtly shaping cultures and fostering mutual understanding.

I’ve often heard foreign travelers asking restaurant staff how to pronounce dish names in Chinese. When people are truly interested in a culture, they are curious and eager to learn more. Rather than retreating into an information cocoon, we should embrace the chance to share China’s culinary heritage.

Editor: Cai Yiwen; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)