The Punk Rock Legend Who Became C-Dramas’ Unlikeliest Fan

There are many ways to kill a conversation — or even end a friendship — in China. One such method is telling your highbrow friends that you’re a fan of Chinese TV dramas. Although C-dramas have gained traction on streaming platforms and even attracted an international fanbase in recent years, they are still widely derided among a certain educated class in China for their formulaic plots, narrow visual language, and unnecessary episode padding. Even the best are rarely grouped with the sleek, sophisticated shows coming out of the United States, the United Kingdom, or South Korea.

Often, these views work like cultural markers. I still remember a university recruitment event over a decade ago, where an established lawyer, his voice firm with authority, told the audience that he ended each day with a single episode of an American TV series. He wasn’t just sharing his viewing habits. He was signaling his advanced cultural literacy. Admitting to a C-drama obsession, on the other hand, would feel like confessing to bad taste — or even worse, a surplus of leisure time.

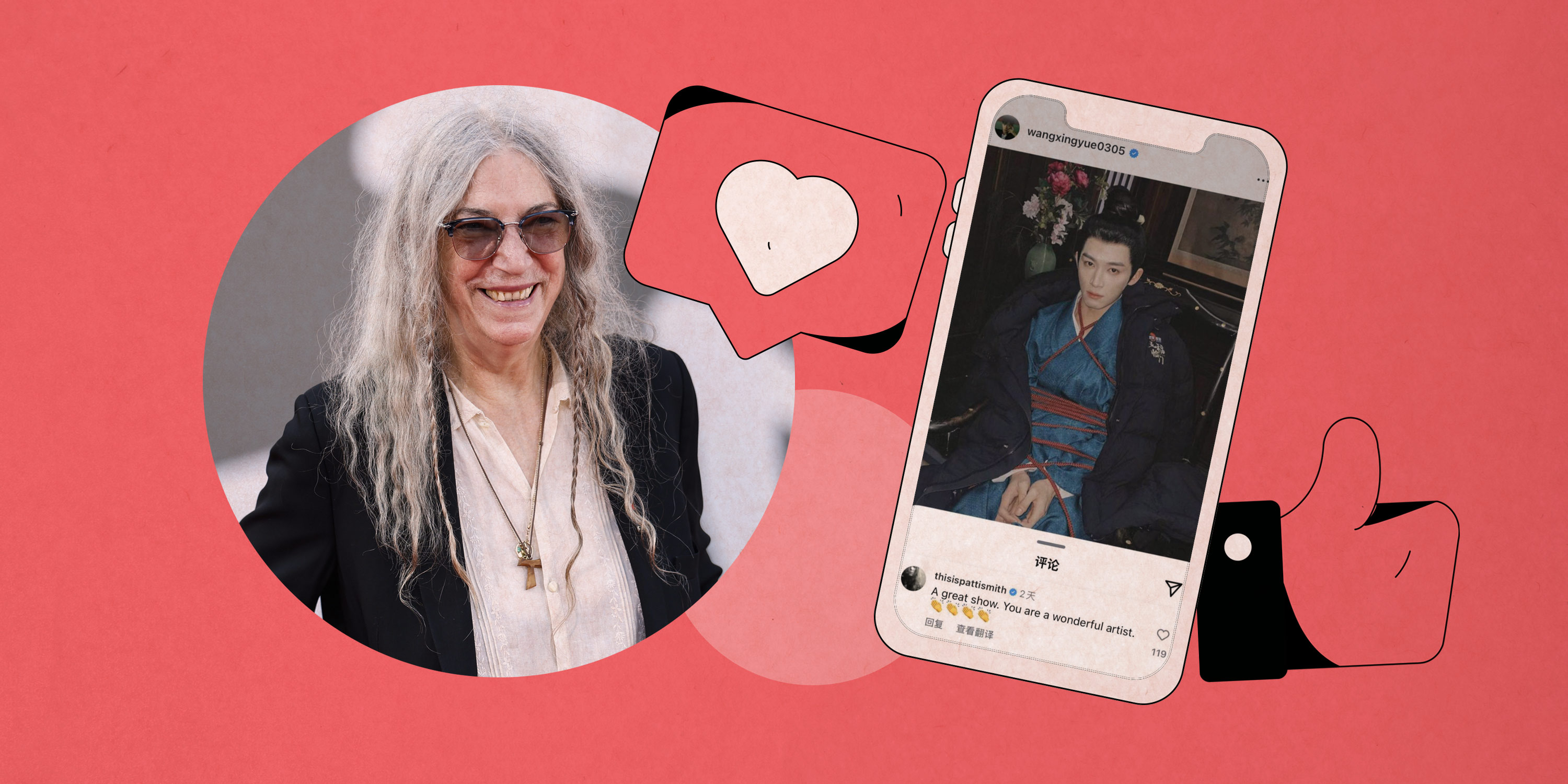

So it came as a shock to many Chinese social media users when the American songwriter and poet Patti Smith — sometimes referred to as the “Godmother of Punk” — liked and commented on an Instagram post by C-drama actor Wang Xingyue about his latest show, “A Perfect Match.” Punctuating her post with four clapping hands emojis, Smith wrote: “A great show. You are a wonderful artist.”

The discovery sent fans of the genre into a tizzy. For fans, Smith’s support came as vindication. “Iconic poet/punk rock legend Patti Smith is just like us!” wrote one poster on a C-drama subreddit. But among the long-time gatekeepers of Western pop culture in China, Smith’s sentiments seemed inexplicable. Wang, 23, has appeared in only a handful of series and remains relatively unknown even domestically. Smith, 78, is a towering figure who has left her mark on poetry, music, and prose alike. It was as if Jane Austen had complimented a minor character actor on “Bridgerton.”

My first thought was whether Smith would still have left that comment had she known about the cultural snobbery surrounding C-dramas. I think the answer is yes. As someone who pioneered New York’s punk movement in the 1970s, Smith understands better than most what it means to find art — and artistry — in unlikely places. Punk’s flamboyant fashion, rebellious hairstyles, and body modifications made it a target of ridicule in its early days, but none of that stopped it from inspiring generations of artists who, like Smith, drew power from its imagery.

It’s funny how an offhand comment by a true legend can force us to reevaluate a particular show or artist, or make us reconsider the line we draw between highbrow and lowbrow. Online, Chinese discourse is often dominated by bishilian, or “the chain of contempt.” Travelers to Africa are seen as superior to those who visit Europe and Southeast Asia, who in turn look down on domestic tourists. The same pattern applies to TV. A 2023 study found that on Douban — a Chinese social media website often associated with fussy users — viewers overwhelmingly preferred British and American dramas, followed by Korean and Japanese shows, with Chinese productions lagging far behind.

I’m not advocating for cultural relativism here. Many C-dramas are repetitive and dull. But should we judge a piece of culture merely by its genre? Consider K-pop. In a recent interview, Yale scholar Li Tian explained that K-pop was initially associated with “bad taste” when it was introduced to the U.S. Today, it’s a key pillar of Korean soft power thanks to acts like Blackpink and BTS. Similarly, in China, critics who prided themselves on their “sophisticated tastes” often dismissed the popularity of K-dramas as a sign of poor educational background. That’s until a 2014 survey conducted by the streaming service iQiyi challenged this stereotype, revealing that 58% of viewers of “My Love From the Star” held at least a bachelor’s degree.

Likewise, brushing off Chinese television means missing out on the political intrigue of “Nirvana in Fire,” or the dark plot twists of shows like “The Bad Kids” and “The Long Season.”

Okay, so maybe I just confessed to having too much time on my hands. But the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu famously believed that distinctions in taste were a way to reproduce social status. We shape our preferences to fit within specific economic and social contexts, and demonstrating refined taste helps one gain acceptance into elite circles. It’s why hobbies like equestrianism and golf can serve as gateways to upper-class social circles — and why a generation of Chinese carefully cultivated their TV-watching habits to seem current in global pop culture.

But rejecting certain genres doesn’t automatically make us superior. At a time when Hollywood feels stagnant, with many mainstream studios relying on franchises adapted from video games or comic book IPs, it’s worth looking for inspiration in overlooked corners of the global entertainment industry. The emergence of new cultural powerhouses can mean more than just fresh entertainment, too. K-pop, for example, has challenged traditional notions of masculinity.

What struck me while reading Smith’s memoir, “Just Kids,” was how vividly she could recall falling in love with pieces of art decades ago — and how rarely she talked about art she disliked. That’s not just positive thinking, but a reflection of how a true artist maintains a childlike sense of wonder, rather than dismissing entire forms of art based on outdated stereotypes.

If Patti Smith, at 78, can still take pride in being “just a kid,” why are the rest of us trying so hard to act like grown-ups?

(Header image: Visuals from VCG and Xiaohongshu, reedited by Sixth Tone)